Associated albums

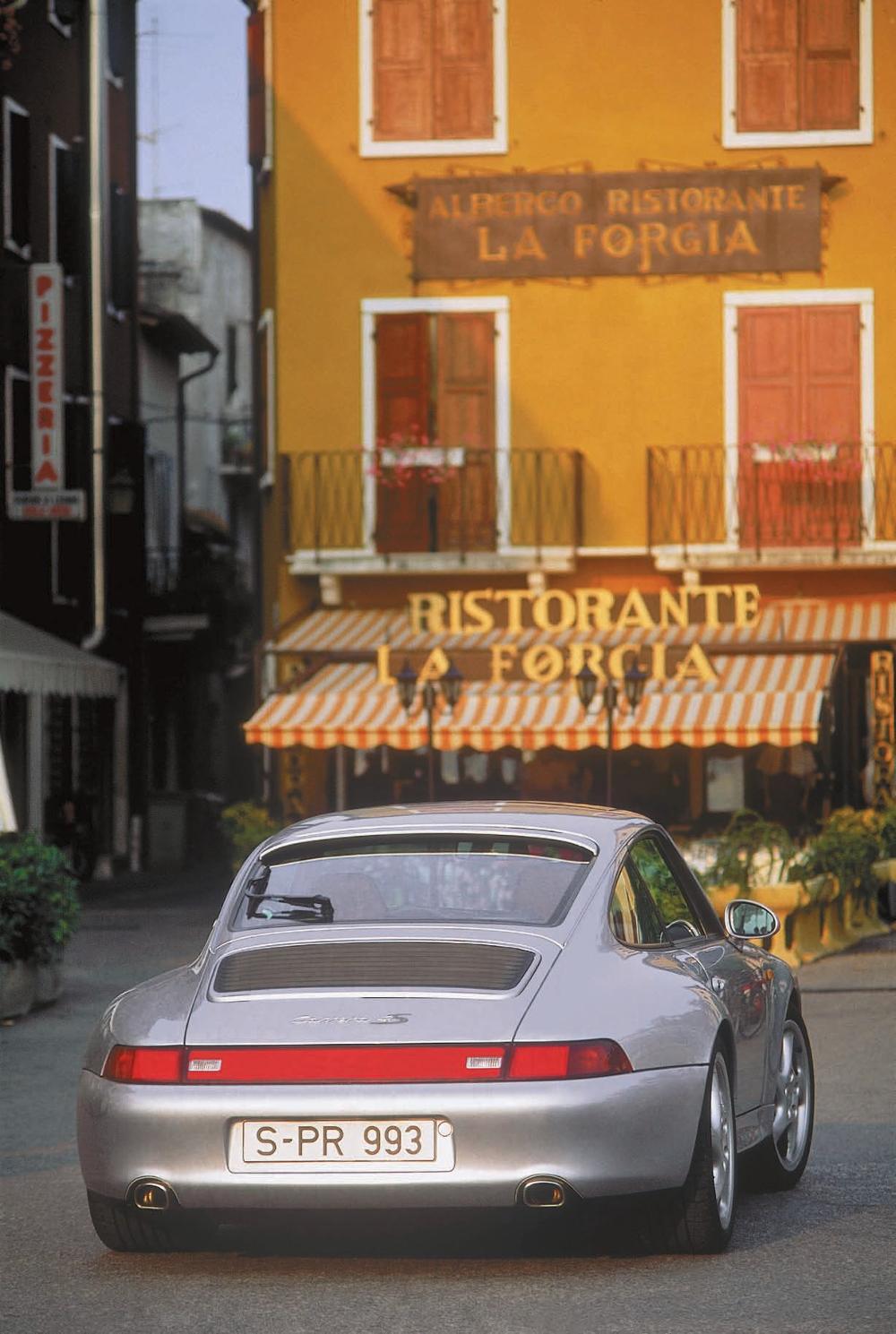

Porsche widened the bodywork by about five inches to accommodate much wider wheels and tires. For brakes, the engineers incorporated ventilated aluminum rotors with dual-piston calipers in front and ventilated cast iron rotors in back. Spacers widened front track by 0.83 inch and 1.1 inches in the rear. Not only were Ampferer’s dreaded air conditioning and rear wiper standard equipment, but sales and marketing also wanted full-leather upholstery, a four-speaker stereo system, electric window lifts, and automatic heat control. Porsche debuted the car at the 1973 Frankfurt show and deliveries began early in 1975. Despite the Turbo’s distinctive rear wing—some called it outrageous at the time—trim on all the 1975 models was otherwise subdued. Headlamp bezels and exterior mirrors matched the body color, and on the Targa, the bar went flat black. In addition to the high-performance Turbo, the company offered base 911, 911S, and 911 Carrera models as well as a special 25th anniversary edition that they painted silver with blue/black leatherette inside to commemorate a quarter century of manufacturing automobiles in Zuffenhausen. Carrera and Turbo coupes ran on Fuchs wheels, while base and S models introduced cast-aluminum wheels from ATS that quickly earned the nickname “cookie cutters.” For 1976, Porsche shuffled its model lineup, dropping one version, resurrecting another, and introducing a third. The base 911 carried over, but now it ran with 2.7 liters tuned to produce 165 horsepower. The 911S disappeared while the Carrera adopted the same 3.0-liter block that powered the Turbo. In its normally aspirated configuration, it provided buyers with 200 horsepower. Both 2.7- and 3.0-liter engines got new cooling fans, not quite one inch smaller in diameter, and with five blades instead of 11, but that turned faster. For a single year, the company reintroduced the 912 strictly for the American market. Full compliance with emissions and safety regulations for the new 924 was a year away. Porsche launched the new coupe in late 1975 as a 1976 model in Europe. In the interim, the 912E used the 2.0-liter flat four of the recently discontinued 914/4. The fuel-injected engine produced 86 horsepower. Porsche manufactured 2,099 for the States in coupe and Targa versions.

Weissach engineers added thermal reactors, a kind of first-generation catalytic converter, and secondary air injectors to the engines of its 1977 model year cars destined for Japan, Canada, and the United States. Vacuum brake boosters appeared on Carrera 3.0 and Turbo models as well as base 911s fitted with the Sportomatic transmission. While the Carrera shifted to ATS wheels as standard equipment, the Turbo became Porsche’s first model to run on 16-inch wheels and tires. Ahead of the rear wheels on the wider body, Porsche added a matte black material to protect the paintwork from rock chips. Inside all the cars, buyers were pleased to find two new air vents in the center of the instrument panel and rotary knobs set into the door panels that locked and unlocked the doors, eliminating the pop-up buttons that a skillful thief could open with a coat hangar.

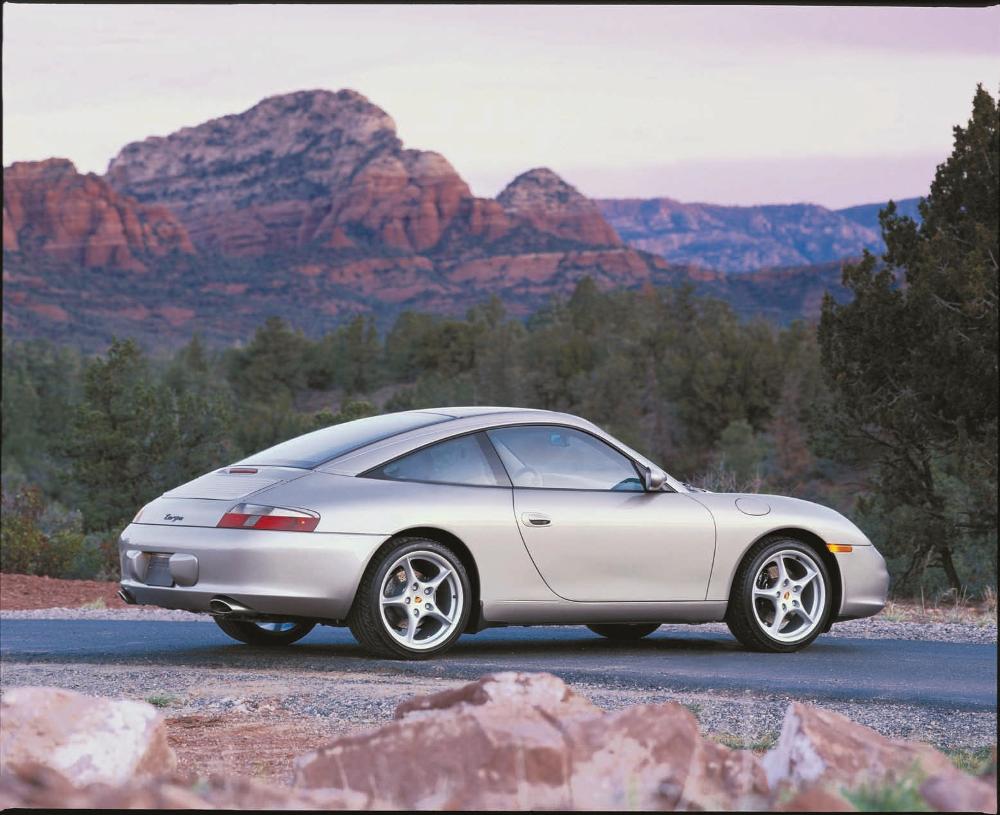

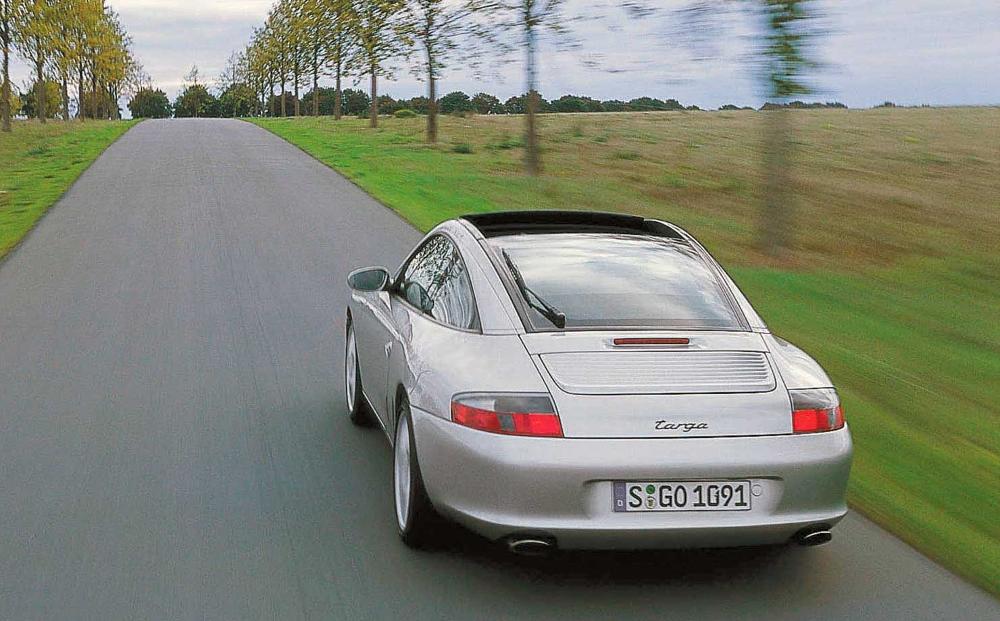

Porsche’s model lineup raised eyebrows in 1978 with the addition of its startling new 928. Outside observers saw a product range leaning toward front engines and water-cooling. The 911 became the new SC model, but in some eyes this was just the next Porsche where the 924 and 928 were the new ones, illustrating the company’s direction. Only two variations of the 911 remained, the SC, standing for Super Carrera, and the Turbo, each with newer, larger displacement engines. The SC took over and improved the 3.0-liter version from the previous Carrera, while the Turbo grew to 3.3 liters. The base 911 and Carrera were discontinued. In its earliest iterations, trim on the SC returned to bright work, with door handles, window frames, and headlight frames all chrome plated. Fifteen-inch ATS aluminum wheels came standard while 16-inch Fuchs were optional. For the SC, Weissach reworked its three-liter engine to provide drivers with greater torque at nearly all engine speeds. As a result—and combined with the effects of mandatory use of regularoctane gasoline—the engine developed 180 horsepower, down 20 from the previous Carrera even as urban drivability improved. Cooling duties called for reinstating the 11-blade fan, but it retained the smaller diameter. For the new Turbo, engineers increased bore to 97 millimeters and stroke to 74.4 millimeters with a new crankshaft. With compression set at 7.0:1, horsepower output rose to 300, though emissions requirements and the need to operate on unleaded fuel in Japan, the United States, and Canada reduced engine output for those countries to 265. Still, it remained Porsche’s most potent offering compared to the 125-horsepower 924 and the newly introduced 240-horsepower 928. Wisely, Porsche’s product planners and marketing and sales staffs still believed that nothing should eclipse the output of the Turbo as company flagship. After three years of chrome, Porsche returned to body colors on the headlight surrounds, while door handles and window frames went flat black for 1979. The compromises in engine timing that had given the 1978 SC good performance at the expense of fuel economy were adjusted for 1979. Horsepower remained unchanged at 200 for the SC, 265 for U.S., Canadian, and Japanese Turbo models, and 300 for rest-of-the-world buyers. Production for the year was 9,475 coupes, Targas, and Turbos. The car was safe for another year.

PLENTY TO DO NOW But the addition of two new cars provoked comment. Throughout 1977 and 1978, Fuhrmann, as not only chief of engineering but company spokesman, answered or avoided questions about this apparent evolution. In early 1978, with 928 models on the road, he quantified the future of the 911. At that time, Porsche manufactured around 45 of the 911s each day. The inquisitors, of course, did not have Fuhrmann’s understanding of engineering, of the challenges to cleaning the emissions from air-cooled engines, of reinforcing the 911 platform to withstand even more demanding impact tests. By 1978, the 911 was close to the same age—13 years at that point—at which Ferry launched the 356 replacement. And how were Fuhrmann’s engineers and designers expected to make something this old seem fresh and new? “The car was still selling,” he explained in 1991. “We still made money from this car. So I set a low limit at which we no longer make money. I told journalists if we ever go below 25 cars, some number each day, 6,000 a year, we stop.” In some sense, though, Fuhrmann already had stopped. He had halted any further engineering, other than what the United States required to continue shipping cars there. Sales in America still accounted for half of 911 production, so, depending on exchange rates, half or more of Porsche’s profits came from American customers. Fuhrmann couldn’t ignore them; he only hoped to entice them into 924s and 928s.

Loyalist groups developed in Zuffenhausen and Weissach. The 911 faithful became outspoken that engineering development and design updates were perpetually shelved. While design chief Tony Lapine drove a new 928, Wolfgang Möbius stayed with his 911 as his company car. Modest engineering changes gave the SC engine an eight-horsepower increase for rest-of-world models, and the Turbo fitted a new exhaust with twin pipes. U.S.-destined cars received catalytic converters and oxygen sensors that sapped away the eight-horsepower gain, and adding insult to injury, new speedometers read only to 85 miles per hour as the States enforced the widely ignored 55 mile-perhour national limit. Porsche stopped distributing Turbos to Japanese, Canadian, and U.S. buyers.

Production of all 911s hit 9,943 for 1980, a figure slightly more comfortably above Fuhrmann’s death sentence. However, budgets for engineering and design and advertising and promotion had to be split in three portions, and to many inside the company and outside, it seemed as if the boss had said one thing but intended something else. During an interview in 1991, Fuhrmann admitted that he had enemies and he felt sure he made some of them himself. People judged him harshly for assuming Ferry Porsche’s role as company spokesman. Those who knew Ferry well spoke of an introverted and circumspect man who shunned the limelight. With his own traits in mind, Ferry had moved his office from the upper floor of Werk I to another building several miles away in Ludwigsburg. People wondered if he went in order to give Fuhrmann room to manage or because he felt pushed out. Ferry’s decisiveness as a leader was beyond dispute. He brought the 356 and the 911 into production. He launched and supported racing programs that made the 550 and the 718, the 904, and half a decade of his nephew Ferdinand Piëch’s race cars into regional, then national, and then international champions, and they became the stuff of legends and articles. He controlled and directed his fractious family in the pivotal meeting in 1970 that removed them—and his probable successors—from jobs within the company. He was 61 at that time, and by age 70 in 1979, he had been an exile from his own company for perhaps six years. Fuhrmann in 1991 told a story about visiting Detroit to drum up engineering business for Weissach after VW’s contract with them ended. He met with Lee Iacocca at Ford Motor Company who was interested in what Porsche might bring to Ford. By the time Fuhrmann got back to Stuttgart, Iacocca had been fired. What Fuhrmann did not add in his recounting of the Detroit tale was that Henry Ford had come to resent the fact that while his name was on the building and most of the cars that left it, when Ford Motor Company spoke, it was Lee they heard, not Henry. What Fuhrmann knew, however, was that Ferry was the opposite of bombastic, outspoken Henry. A decade younger than Ferry, Fuhrmann looked forward to his 60th birthday coming up in 1979. Sales of his 924 and 928 were growing. By 1980, the 911 was heading to its 15th anniversary. He was convinced that the company needed a new car. “Work was a little slow,” he explained. “At that time we should have begun a new program.” He went to Ferry to explain that he didn’t want to work until the end of his life, that a new car took seven or eight years to reach the market, and he wanted to stop at 65. He told Ferry he was prepared to leave the day Porsche had a new man who could launch a new program. Ferry got busy. Through headhunters he approached Bob Lutz who ran Ford of Europe for several years. Ford shipped more of its Fiesta compacts to the United States than Porsche had produced in all three models during 1979. Ferry had labor problems and disappointing sales. He was unable to articulate the future he saw for his company. Lutz, one of twelve candidates for the job, stepped away. But, true to his word, Fuhrmann went home to Austria before year-end.

Previous Page

Page 11

Next Page