Associated albums

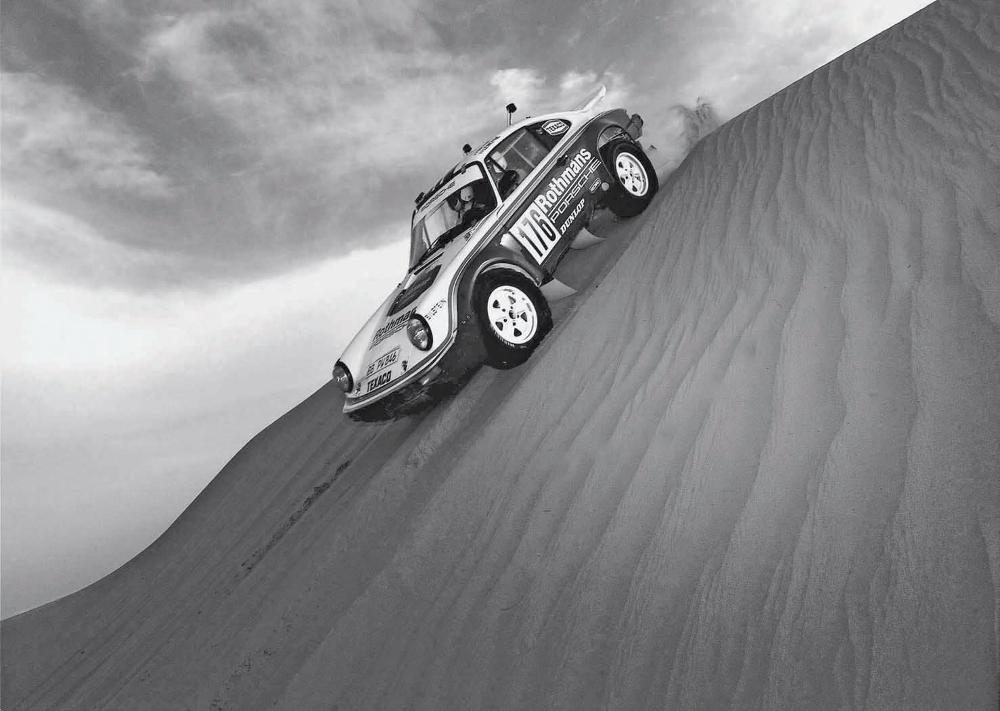

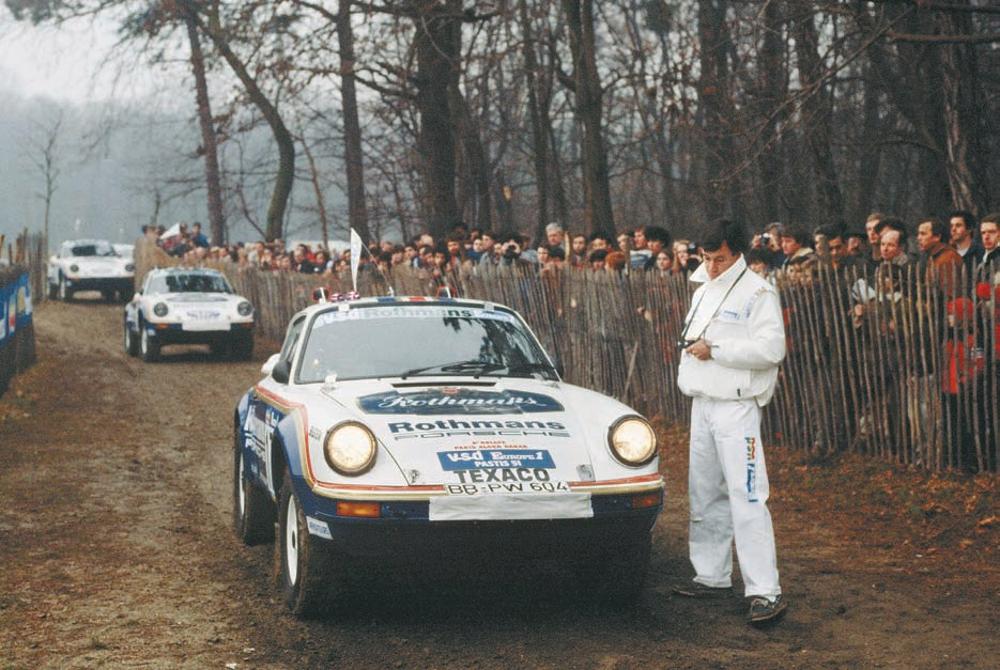

THE FOURTH GENERATION: 993 “I didn’t think they would ask me to come back,” Harm Lagaay said in an interview near his retirement home at Inning, southwest of Munich. “But when they asked me, I definitely had a very strong plan. I knew what Porsche was, what they had been in the 1970s.” Lagaay was there in those days, arriving in time to see Piëch’s radical mid-flat-six engine proposal and all its variants. Lagaay had styled the VW EA425, which became, after VW stepped away, the Porsche 924, and he left in 1977 soon after the car launched. “I thought: This is what they need. They definitely cannot go on with the 964. . . . Nothing was right anymore.” With the 911 under F. Porsche and F. Porsche Junior and F. Piëch, the car came to life, and as it advanced, it defined sports car performance and appearance. When Fuhrmann arrived, the car entered a period of benign neglect (though it’s likely Bott and others felt this was more malevolent) until Schutz, the 911’s champion, arrived. With Schutz, the 911 played catchup. And then it rocketed ahead. The 1983 SC Cabriolet was the world’s fastest production convertible. Four years later, the 959s routinely touched 200 miles per hour on German autobahns. Notwithstanding its financial costs and the management upheaval it precipitated, it had one other fault: it looked startling, like an automobile from another planet. Not the next Porsche, but the New 911. The 959 put gray hair on the G model and, while engineering and design changed the 964 in many ways, it looked like the next 911, not the new Porsche.

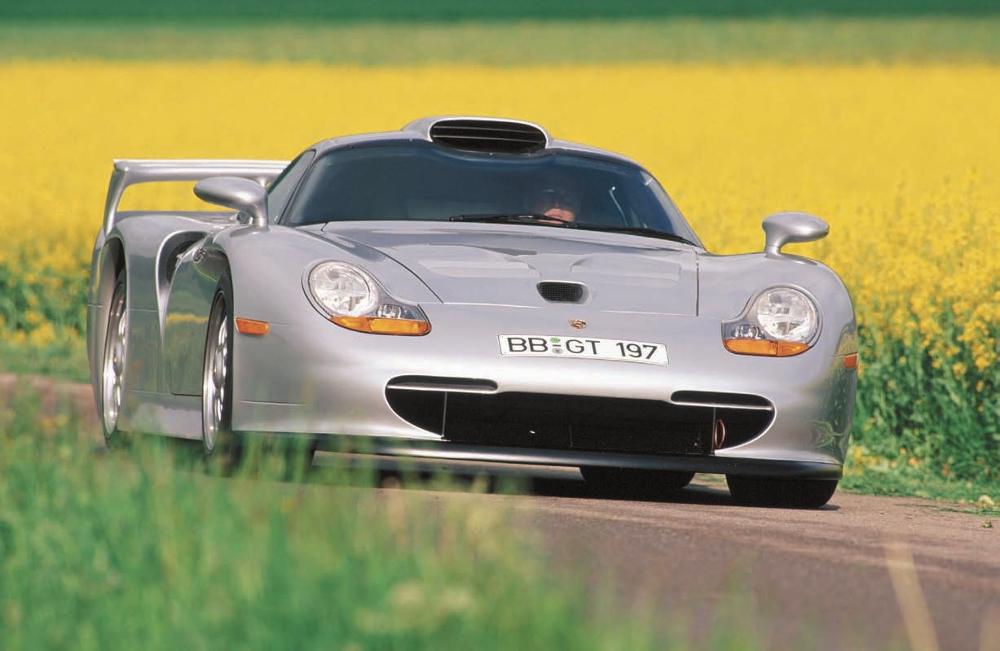

“I am not someone who is afraid of changing the 911,” Lagaay continued. “On the contrary, I was absolutely convinced that it had to change radically. We started the 993 immediately after I arrived.” This was 1989, the year of Ferry Porsche’s 80th birthday, a natural anniversary for a special car for the founder. Lagaay gave the styling assignment to Steve Murkett, who had joined Porsche in 1983 and had admired the 928 since its introduction, and had completed the production version of the 959. Styling cues from both those cars—and from Murkett’s fascination with off-road vehicles and dune buggies—inspired and appeared on the 1989 Panamericana, a very radical glimpse into Porsche’s future design language intended first as a Frankfurt show car to spotlight Porsche’s new four-wheel-drive series cars. To change the 911, Lagaay assigned Tony Hatter to style its exterior and he pulled cues from the ill-fated 965 Turbo. Across the compound in Weissach, Ulrich Bez, as Bott’s successor, was firing up—and some said—igniting his engineering staff. The new 993 had to be less expensive and less time-consuming to manufacture. It had to look better, perform better, weigh less, emit less, and do all this by last week. Because Bez expected all the development work he had scheduled to see tomorrow on the new four-door sedan, the Typ 989, to be completed by noon yesterday. Bez, fresh from a decade at BMW developing the Z1 sports car and future sedans, intended Porsche’s four-seater to take the company up market and to set new benchmarks for engineering accomplishment.

Herbert Ampferer’s engine group, resigned to carrying over the 3.6-liter engine from the 964, nevertheless made significant improvements. They eliminated a troublesome torsional vibration damper from the crankshaft. They reduced valvetrain weight and incorporated self-adjusting hydraulic valve lifters. They redid the entire exhaust system. All this work gave them an engine that developed 272 horsepower at 6,100 rpm and was quieter than any 911 engine before it. Engineers reconfigured the G50 transmission to add a sixth gear, lowering the ratio on first and stretching the new top gear to get the car to 168 miles per hour. It has been said that engineers design a car from the inside out and stylists conceive it from the outside and work in. With the 993, both procedures got polished and proven. “ I didn’t think they would ask me to come back. But when they asked me, I definitely had a very strong plan. I knew what Porsche was, what they had been in the 1970s.” — Harm Lagaay

REAR STEERING THE 993 “We designed the rear suspension for 993 from 964,” Bernd Kahnau explained. “At that time we had the idea in Germany that all cars needed steering on the rear axle, all-wheel steering. That was the idea and we made an axle for the 993. But it was only drivable with four-wheel steering. Then two years before starting production, we decided it was not a good idea. So we had nothing to work with.” Engineering colleague Georg Wahl came to them. Working for Bez on the 989, he and his team had developed the steering rear axle for the sedan (and intended for the 993), but after that was stopped for costs and weight, they were forced to develop a replacement, which he offered to Kahnau’s group. “We threw away the idea of rear steering. We had the subframe, that was necessary to make the rear-steering work, and this new axle was alloy, lightweight, and it made for a very comfortable ride. It improved the handling,” Kahnau said. Because Wahl’s group had developed it under budgets for the 989, it cost Kahnau’s 993 team nothing. The new rear axle assembly yielded another benefit. “We made the 993 so that we really didn’t need the four-wheel drive,” Kahnau said. “With the new axle, the new platform, the rear engine, you don’t need four-wheel drive, even in Switzerland in the snow. But we went into special markets, like Austria, Switzerland, like Sweden, and they said, ‘We need four-wheel drive.’ They didn’t, but we redesigned the front drive system for the Carrera 4 models for them.” The engineers replaced the heavier 964 configuration with a viscous coupling at the transaxle, connecting a torque tube to a compact, exposed front differential that sent power to each wheel. The new system saved 110 pounds over the 964, further benefiting ride and handling.

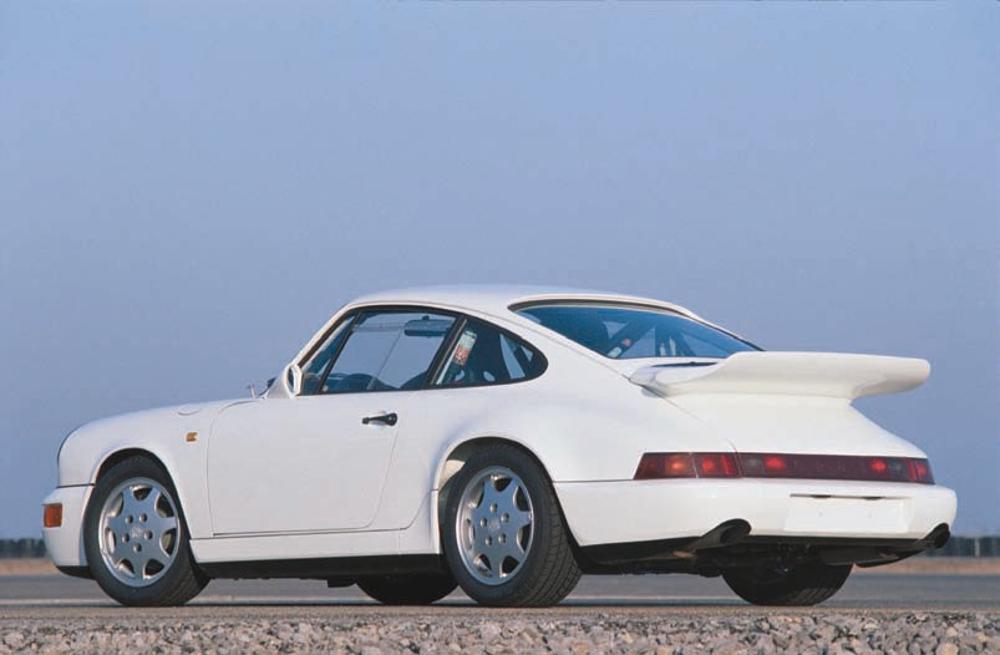

For stylist Hatter, his goal was to address the proportional balance of the 911, something he and others felt had gotten slightly off with the 964. “I always like to compare the forms to muscles,” he explained, “forms with a lot of surface tension to them, not just rounded biological forms. There are no shapes or forms on the cars that don’t have to be there. The bulges, that’s where the wheels are. You can see where the people sit.” Not everyone was immediately thrilled with the new look. “I remember F. A. Porsche came a week or two weeks before Christmas,” Bernd Kahnau recalled. “I was supposed to show the 993 to him. He sat in the car and said nothing. Five minutes. “‘Mr. Porsche? Is it not good what we have made with the 911?’ “Papa doesn’t see the fenders,” F. A. replied, referring to Ferry’s styling edict that he must see the fenders to know where his front tires were located. Aside from a few such moments, the 993 largely escaped acute scrutiny. “It was a fantastic time for us,” Kahnau continued. “Mr. Bez, he had the F1 [efforts with Footworks] . . . and all the executives, the first team, paid attention to the 989. And nobody paid any attention to those of us who made the 993. We had it all to ourselves. We all knew something important, however: if it is not good, we are dead. It was not very simple for us. But what I know now is that the best years we have made the 911 is when the rest of the company is making another car.”

THE ARNO BOHN ERA Through all this time, the personality and perspective in the front office changed. Heinrich Branitzki, who had hoped the 964 would endure for a quarter century, was gone barely a year after expressing that ambition. On March 4, 1990, a former computer company director, Arno Bohn, who only had joined Porsche’s board at the beginning of the year, became Porsche CEO. By the time the 993 reached the market, the struggling economy—and difficult personalities—had caused more leadership changes. Bez, pushy and imperious, was forced out in late 1991. Bohn, the wrong man in a difficult place at an impossible time, was released from his contract in late September 1992 as the company teetered toward bankruptcy. In a magazine interview, Ferdinand Piëch recommended that Ferry Porsche should retire; soon after, Bohn, supporting Ferry, wrote to Piëch suggesting he resign from Porsche’s supervisory board. Instead, Bohn was gone within weeks. Wendelin Wiedeking, who had returned to Porsche in 1991 to head production, became company CEO two years later, as the 993 neared production start.

THE WENDELIN WIEDEKING ERA In a now-legendary confrontation with Porsche tradition, Wiedeking enticed two former Toyota executives to bring the philosophy of kaizen, or continuous improvement, to company manufacturing and to teach them efficiency in production. Calling the existing factory facilities “warehouses” because stockpiled parts occupied as much floor space as assembly lines, the Japanese inspired Wiedeking, who eventually reduced assembly floor inventories from 28 days on hand to 30 minutes, forcing Porsche’s outside vendors to adapt or fall off the preferred suppliers list. The streamlined Zuffenhausen operation manufactured 2,374 of the new 993 coupes—and 221 pilot production cabriolets—by the time Porsche closed for its Christmas/New Year holiday break at the end of 1993. Labeled as 1994 model cars, they began deliveries to European customers in April. The first American buyers saw 1995 models in September 1994. The cabriolet roof presented challenges to Tony Hatter and the design engineers he worked with. Gerhard Schröder’s top system designed for the 1983 SC passed largely unchanged through the 964 models. Hatter was not a fan. “I never liked the look of the early cabriolets. The classical 911 shape is the coupe. With the 993, we tried to get some of that form into the roof.” The 993 was the first time designers or engineers had been allowed to revise the cloth top. Production for the first year reached 7,865 coupes and 7,074 cabriolets. For all of their dramatics, the efforts of Ulrich Bez and Wendelin Wiedeking delivered benefits to customers—with a base price $5,000 less than the 964—and profits to the company, incredibly. The new car helped rewrite Porsche’s financial statement as the economy finally returned to solid footing in 1995. By this time, Porsche had begun delivering all-wheel-drive Carrera 4s. Weissach updated and revised the Tiptronic transmission, renaming it the Tiptronic S; however, it was available only for rear-drive models.

Previous Page

Page 16

Next Page