Associated albums

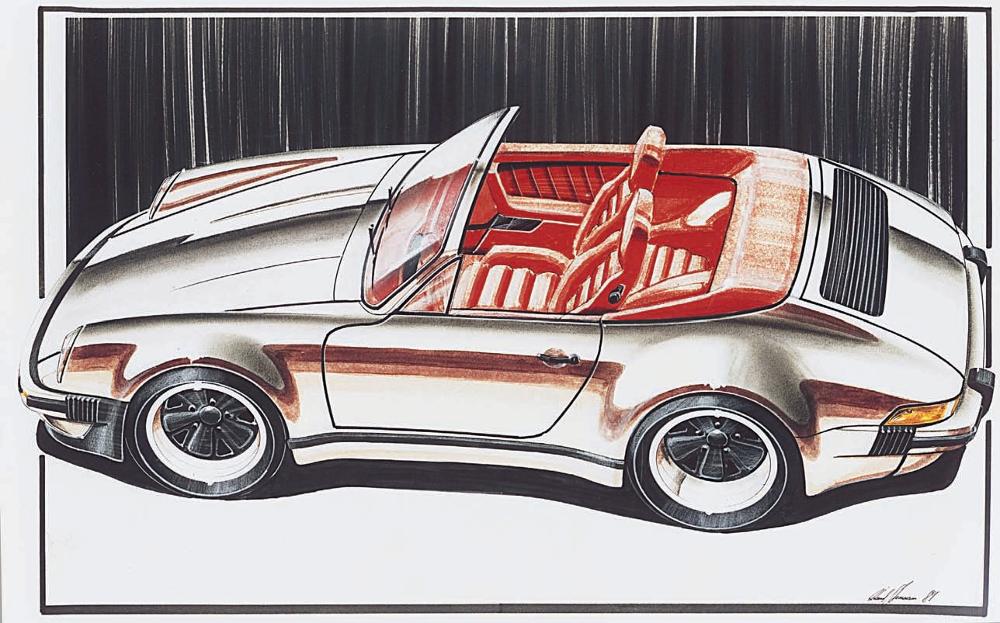

EVOLUTION VERSION 1.0

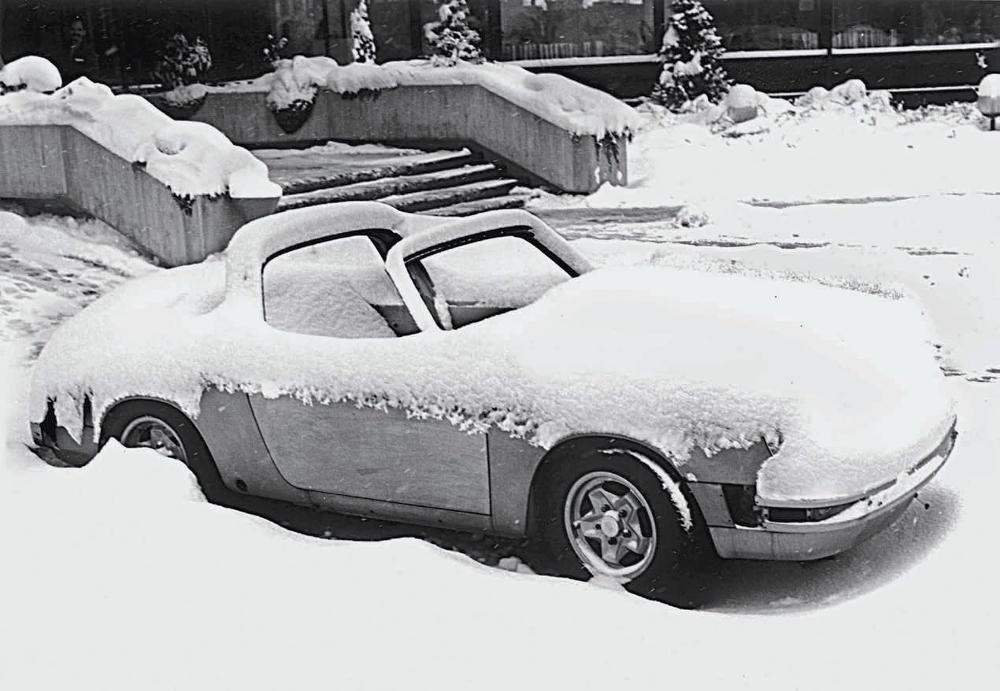

Throughout the ascent of design Typ numbers from 695 to 754 to 901, Ferry remained committed to offering an open version of the new Porsche. F. A., his designers, modelers, and engineers had submitted three scale drawings and a model to Ferry, who followed up this review with a letter he wrote to Karmann in mid-October 1962. Karmann assembled the 356C and SC cabriolets and was the natural one to field this inquiry. Ferry asked the manufacturer to evaluate the concepts, which included a cabriolet system similar to the 356 configuration with a padded top, a clear plastic window removable by zipper, and a boot that hid the roof and stored it as low as possible in the car body. The second option was a collapsible top that required unsnapping the cloth material for stowage beneath the boot. The third version described a main top bow housed inside a rollover bar with removable top and rear panels. F. A. also had proposed a rigid but removable steel roof. Still other concepts followed, including one that described a collapsible and/or a removable rollover bar. Perspectives differed on the look of the roof and the profile of the car, top up or down. F. A. told Aichele that he preferred that “the open car should have a distinct feeling in the roof line, to underscore the Roadster feeling.” He offered a drawing in early December 1963 that showed this idea. It was not as severe as the “stepped roof” variations Erwin Komenda had made five years earlier, but it showed a definite, gentle break in the roofline behind the rear window. The roadster concept, however, brought up problems with the entire idea of an open car. As Eugen Kolb pointed out, “No one considered the cabriolet during design of the coupe. It was talked about but forgotten when the other discussions were going on.” Whether a rollover bar collapsed or a soft top folded into the rear of the car, there was no place to put it. One version completely sacrificed the rear seats for the top, its bows, and the rollover bar storage. There were other considerations. Although that recent evolution from an engine with two smaller cooling fans mounted over each cylinder bank to the Typ 901/1 with its single larger one certainly had improved engine performance, smoothness, and reliability, it had yielded one unanticipated consequence. Where Komenda’s 356B Hardtop Coupe had increased interior room for the 356, the B Roadster’s alternate bodyline reduced the space even when the top was raised. Lowered, it proved impossible to store any 911 top proposal because of the taller engine and the chassis parts. “Drawing the cabriolet, the system to open the roof, the kinematics, was not right,” Kolb explained. “The system for the 356 was completely developed, but nothing could be taken from it for the 901. If you had copied the 356 roof system, it would have been too high at the rear, like a Volkswagen, not like a Porsche.” Kinematics studies the mechanics of the motion of a body or bodies—in this case, the cloth top and support bows of a convertible roof—without considering its own mass or forces acting upon it. Most crucially, the estimated costs of designing, developing, and making stamping molds for new sheet metal for this 911 roadster body killed any chance. “ Drawing the cabriolet, the system to open the roof, the kinematics, was not right. The system for the 356 was completely developed, but nothing could be taken from it for the 901.” — Eugen Kolb After the September IAA debut, however, pressure increased. Sales boss Harald Wagner reported that many visitors asked about an open version. Over the next months, development continued on more concepts until early June 1964, when a prototype “open car” emerged from the shops. Gerhard Schröder remembered that Franz Ploch and engineer Werner Trenkler had gotten a car to work on. They also had done cabriolet development for the 356 models. By June 12, he and engineer Werner Trenkler had completed their first mockup, and Ferry had it photographed that day. Barely two weeks later, on the 24th, a group convened to review the car. Ferry Porsche, F. A., Hans Tomala, Hans Beierbach (now running Reutter for Porsche), Erwin Komenda (whom Ferry had put in charge of completing the 901/911 technical drawings), Fritz Plaschka, and Harald Wagner (Ferry’s sales chief) examined the car. Trenkler and Schröder were missing from the review. This was a case, Schröder explained, where those asking the questions asked the wrong people. Had he and Trenkler been present, he said, the story might have a different ending. Wagner argued vigorously for the fully open car, expecting it to sell at least as well as 356 cabriolets had done. Ferry listened as Beierbach and Komenda stressed the extensive work and the expenses Porsche might incur stiffening the chassis and revising the rear body panels to accommodate the soft top and its supporting bows. Ferry concluded that it was too costly, deciding instead to approve the roll-bar variation. However, it, too, needed some changes. “There were so many obstacles,” Kolb continued. “Of course, the car lost much of its stiffness. The cabriolet proved the 901 chassis was not strong enough.” One further consideration affected Ferry’s reluctant decision to let the cabriolet slip away: By this time, automobile safety advocate Ralph Nader in the United States had drawn a growing audience to his objections to vehicle design and engineering. Inside Porsche, engineers, designers, and marketing staff worried that legislators in its largest market might outlaw convertibles altogether.Soon after this, Ferry asked Karmann in Osnabrück, who did not respond to his first inquiry, to work further on an open 901. Porsche shipped them the Ploch/Trenkler prototype, 13 360. When that car returned to Zuffenhausen on September 10, 1964, it entered the system with a Cardex that showed the date, its number, and its specification as a Typ 011/KW, Cabriolet, a designation that modern-day engineers suggest may have been intended to disguise its real purpose. A few days later, Porsche started 901 production, on September 14, beginning with serial number 300 007 (oddly, Porsche did not assemble number 001 until the 17th). With production startup problems occupying his time and energy, it wasn’t until late in January that Helmuth Bott took a long evaluation test drive in 13 360. He paid particular attention to chassis stiffness (which, after Karmann’s work, he found no worse than the 356 cabriolets he had driven), and to the soft rear window flapping and fluttering. A few days later, testing the car with the removable roof panel in place, the wind noise was so great he could converse with a fellow engineer only by shouting. There was work to do.

“ There were so many obstacles. Of course, the car lost much of its stiffness. The cabriolet proved the 901 chassis was not strong enough.” —Eugen Kolb

Trenkler and Schröder addressed each item on Bott’s list, and listened as others, Rolf Hannes of the testing department and design boss F. A. Porsche, added input. Hannes pointed out wind draft problems, and F. A. objected to the way the rubber-coated cloth ballooned up at high speed. For Schröder, this was a personal challenge; he had devised the panels, struts, and supports that kept that from happening with the 356 cloth tops. However, because this “targa” top panel had to collapse for storage, there was little he could do until the later rigid version appeared. On February 1, 1965, the car emerged as the subject of a joint memo to two dozen managers, engineers, and designers discussing a 912 for testing, a right-hand-drive 911 prototype, and the Cabrio, 13 360. A drawing at the bottom of the second page suggested that decisions had been made. This combination of crucial considerations killed the Cabrio and brought about its alternate, a model that marketing and sales named the Targa. Helmuth Bott and his staff had identified specific locations on the 901 unibody that required reinforcement for a cabriolet. They added bracing ahead of and behind the doors, and through the rocker panels. A rollover bar, judiciously disguised, restored a great deal of the rigidity and stiffness to the car. The question was where it was to be located, and what it was to look like. “I discussed with Mr. Schröder how we make this bow,” Kolb recalled. “It must be metal that will not rust. And we have to make the bow stiffer. I kept trying to consider the safety, to make it strong like the metal on the side of a road. He said ‘No, not yet. First we make it look right, and then we can make it strong enough.’ “One day a coupe appeared in the studio.” Kolb and Schröder gathered up some transparent materials and laid them over the top of the car. They roughed in some lines in pencil. Because they were hard to see, Kolb retrieved some black tape from the studio and remade the lines. “And then we began to move lines back and forth to define the bar. Butzi thought it was ugly. We changed the shape, some, just a little, Butzi said okay, and then I started to make the drawings. And the idea of using stainless steel came from Butzi, right at the very beginning,” Kolb said. “It was Mr. Bott,” he continued, “who insisted on the removable soft rear window. He wanted as much as possible to enhance the open car feeling. Then of course,” he went on, “the discussions came about what to call it and how to market it. Was it Porsche’s ‘open car?’ Feelings about the American market prevailed. We promoted it as our coupe with a safety item, as ‘Porsche’s Safety Car.’” As Ferry had done with the 901, he debuted the Targa nearly two years in advance of first deliveries, at the IAA show in Frankfurt in September 1965. Barely a month earlier, on August 11, Porsche had registered the patent for the Targa, No. 1455743, listing designer Gerhard Schröder and engineer Werner Trenkler as its inventors. (Registering this patent was one of Erwin Komenda’s last tasks within Porsche. He had worked with—or for—one Porsche or another for more than 35 years. Colleagues from that time suggest that he changed when Ferry Porsche pushed aside his ideas for the next Porsche. His rebelliousness toward Ferry simply may have been his assessment that no other designer could measure up to his own ideas or to those of Ferry’s father, no matter what their family name was. For several years he had suffered from lung cancer even as he continued working. He left the company in late 1965 and he died on August 23, 1966. He was 62.) “ I discussed with Mr. Schröder how we make this bow. It must be metal that will not rust. And we have to make the bow stiffer. I kept trying to consider the safety, to make it strong like the metal on the side of a road. He said ‘No, not yet. First we make it look right, and then we can make it strong enough.’ — Eugen Kolb Just in advance of the September show, Porsche issued a press release announcing the new model and its name. September proved to be another decisive month for Porsche. The Targa debut was a tremendous success with crowds as excited as they had been two years earlier seeing the New Porsche. Clever and creative marketing promoted the new car as four-in-one: With its roof and rear window removed, this was the Targa Spyder; it was the Bel-Air with its rear window zipped in place but the top open. Reversing that order, with top on but rear window collapsed, earned the vehicle the name Targa Voyage, and completing the lineup, with all panels in place, marketing called the car the Targa hardtop. Ferry, his direction set, discontinued production of the 1600cc S engine as well as the S and SC model cars. Porsche cabriolet manufacture ceased as well, except for a limited run in 1965 for the Dutch highway police. Within days of the end of the IAA, Bott took a Targa prototype to Wolfsburg’s test track for endurance testing. He learned the car needed further reinforcement at the rear doorsills and along the heater tubes. An even more demanding durability test took place in Zuffenhausen on November 10. Bott and Werner Trenkler supervised a drop test on the Targa, inverting a car, hanging it by a crane, and releasing it from two meters above the pavement. If Porsche was going to promote the car as a safety vehicle with rollover protection, Bott wanted to be certain it could handle more than a mere rollover. It didn’t. Trenkler reworked the roll bar, its mounts, and the surrounding structure, as well as the windshield frame, and in early January 1966, Bott returned to Wolfsburg with the improved prototype where drivers ran it longer and harder over the endurance test without any failure. One year later, on January 23, 1967, Porsche began production of the Targa as a 911 and 912 model.

THE ITALIAN ROADSTER EXPERIMENT With no knowledge that the Targa was coming, and with no production Cabrio on the price list, California Porsche distributor Johnny von Neumann took matters into his own hands. He had done that before, teaming up with Max Hoffmann to conceive and promote to Ferry Porsche the sales potential for a Typ 540 Speedster to follow on the heels of the America Roadster in the early 1950s. This time, he bypassed Hoffmann and Porsche altogether, taking his idea to Italy to Nuccio Bertone, who, over the next nine months, designed and fabricated a roadster body on a 911 chassis. Von Neumann funded the work himself, hoping to license the design to Porsche. He was a racer and a consummate salesman, but he was not an engineer, and the project stumbled over obstacles he had not foreseen. He was unaware of how much structural stiffness the 911 chassis lost without its steel roof. What’s more, Bertone’s design, while stylish and appealing, was more Bertone than Porsche. Finally, when von Neumann offered the car to Porsche, Ferry declined it, expressing his concern that the Porsche name had come to represent quality he was not sure could be matched everywhere. The Abarth experience had made Porsche cautious.

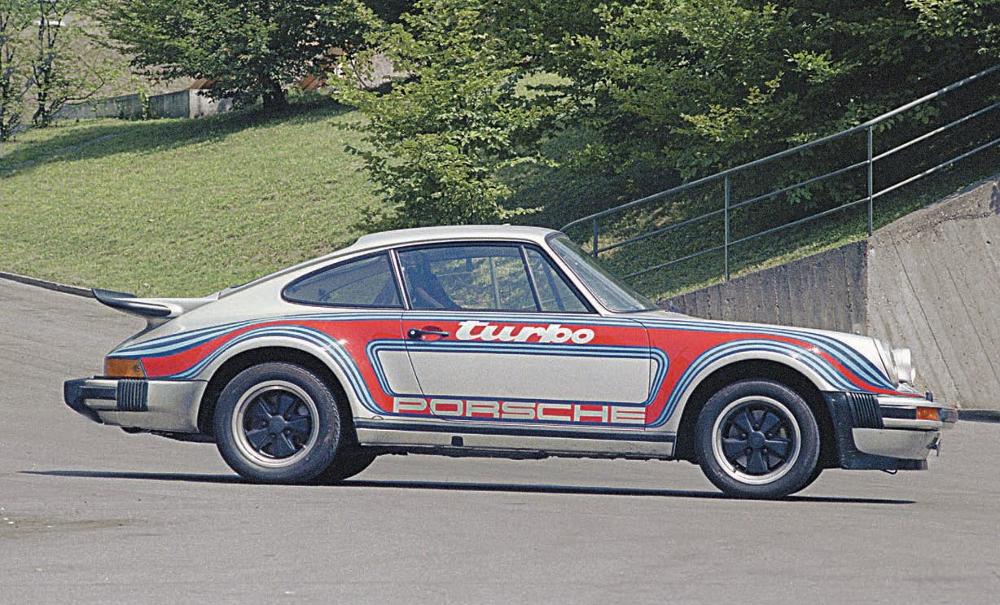

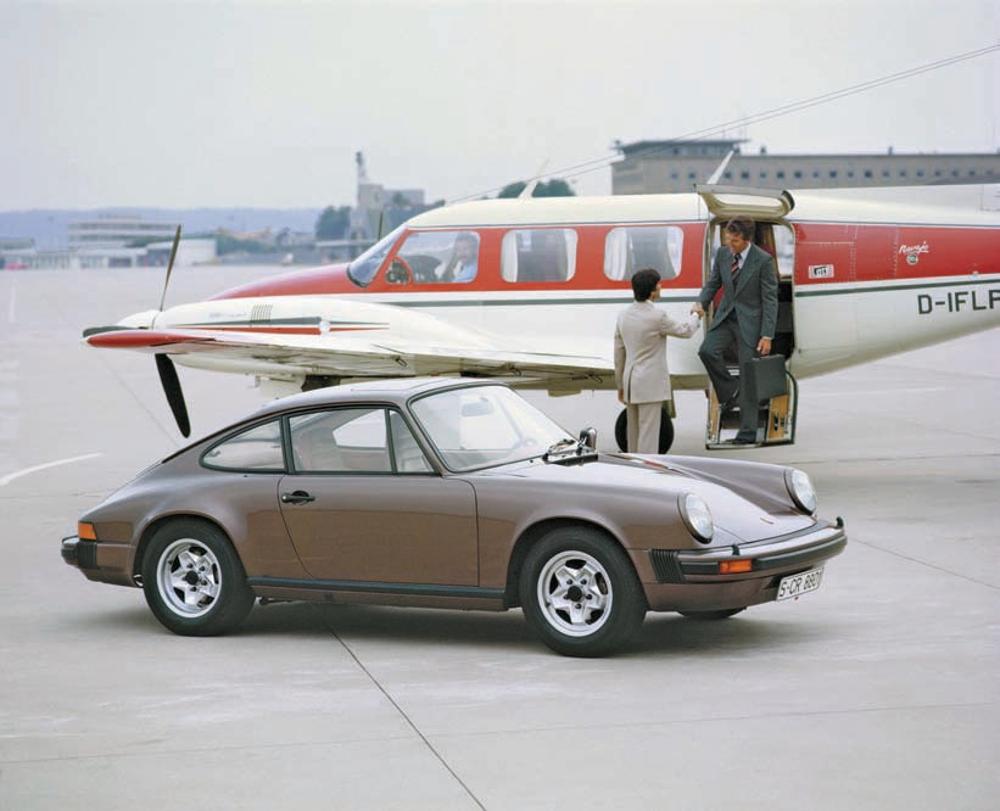

Ferry’s engineers hardly remained idle during these years. As the 356 series had swelled with the addition of Super variants, so the 911 followed suit, introducing the more potent 911S in 1967. This engine developed 160 horsepower at 7,200 rpm out of its 1,991cc displacement. Engine designer Hans Mezger brought new technology to the engine, surrounding the cast-iron cylinder liners with a finned jacket of aluminum to promote better heat transfer to cool the engine. The S was super in many other ways, with its five-speed manual transmission as standard equipment, as well as front and rear anti-sway bars and Koni shock absorbers at all four corners. Porsche introduced ventilated disc brakes and new five-spoke forged aluminum wheels from Fuchs. The other significant 911 variant was the four-cylinder 912 model. Introduced in April 1965, Porsche adapted the powerplant from the 356SC in the car, developing 95 horsepower at 5,800 rpm from the 1600cc pushrod engine. It was a shrewd product on Porsche’s part. Priced some 5,500 DM (roughly $1,375 at the time), less than the 911, it only slightly reduced standard equipment and trim levels. Its body, brakes, wheels, and suspension were nearly the same, and many drivers were quick to point out the four-cylinder car’s better handling with its lighter engine at the rear. While the 912s came standard with a four-speed transmission, the extra cost five-speed was a popular option because it improved performance and fuel economy. Ironically, because it was such a frequent choice, at the same time Porsche introduced the 911S with a five-speed in 1967, it made the transmission standard as well in the 912. “ It was Mr. Bott who insisted on the removable soft rear window. He wanted as much as possible to enhance the open car feeling. Then of course,” he went on, “the discussions came about what to call it and how to market it. Was it Porsche’s ‘open car?’ Feelings about the American market prevailed. We promoted it as our coupe with a safety item, as ‘Porsche’s Safety Car.’” — Eugen Kolb Throughout this time and for decades before, Porsche’s engineering staff had served under contract as Volkswagen’s research and development division. One of Ferry’s key motivations for acquiring the land and building the facilities at Weissach was to better serve VW as well as other clients who came in search of Porsche’s expertise. Being a shrewd businessman, Ferry organized Weissach so that VW’s annual contract met its operating overhead. Any other revenue was profit. With this kind of freedom, Weissach became a think tank and brainstorming center as well.

Previous Page

Page 7

Next Page