Associated albums

In Gmünd and then in Stuttgart, Ferry’s sons regularly visited his production facilities, design studios, and engineering workshops. When Goertz arrived, eldest son Ferdinand Alexander was 22. Throughout his lifetime, he was called a variety of names; in later years he was referred to as F. A., though he was better known at home and around the shops as “Butzi.” In written memos circulated to management in the 1950s and 1960s, he was F. Porsche Junior, or just “Junior.” He and his younger brothers Gerhard, then 19; Hans-Peter, 17; and Wolfgang, 14, were familiar faces to all the employees. F. A. had displayed some sensitivity to design, and in the summer of 1957 he spent a fair amount of time in the model shop learning from Goertz and Klie as they worked. It is unclear if F. A. participated at all in the process; however, in a recently discovered photo of that project, the name “Junior” appears on the right front fender—the side Klie modeled—in a generous nod to a contributing collaborator, and a suggestion for a potential name for the next Porsche. A few months later, in the fall of 1957, F. A. entered the Hochschule für Gestaltung (HFG), the prestigious upper school for art in nearby Ulm. It was a short-lived experience, however. As F. A. explained in an interview in October 1991 at his design offices at Zell am See in Austria, he admitted he “wasn’t so good at drawing,” and his young untrained sculpting skills barely were better. The school asked him to leave after his first semester, an occasion that prompted a bit of his own rebelliousness. When he returned to school from Zuffenhausen to retrieve his belongings, he took one of the factory’s Jagdwagens. Fellow students remember that when F. A. reached the school, he found a suitable stair-climbing gear and drove the Jagdwagen up inside the building hallway to load up his possessions.

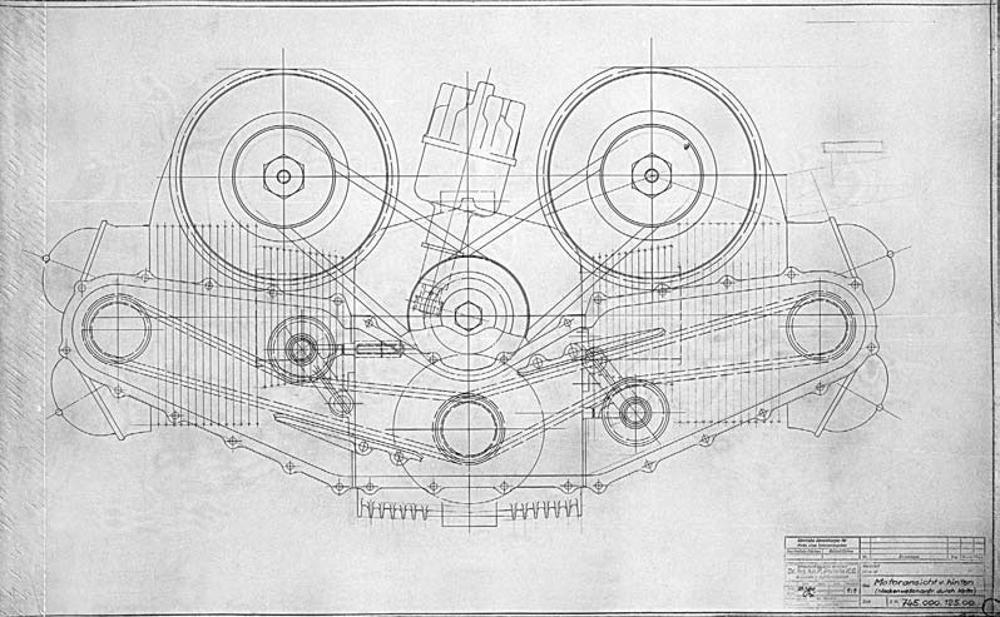

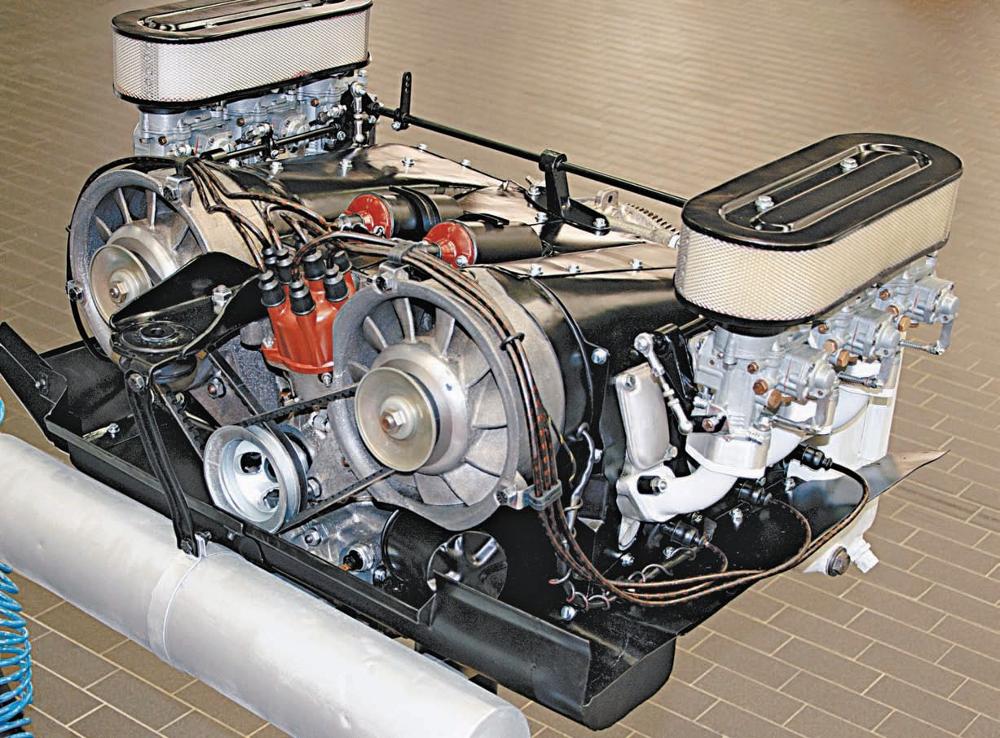

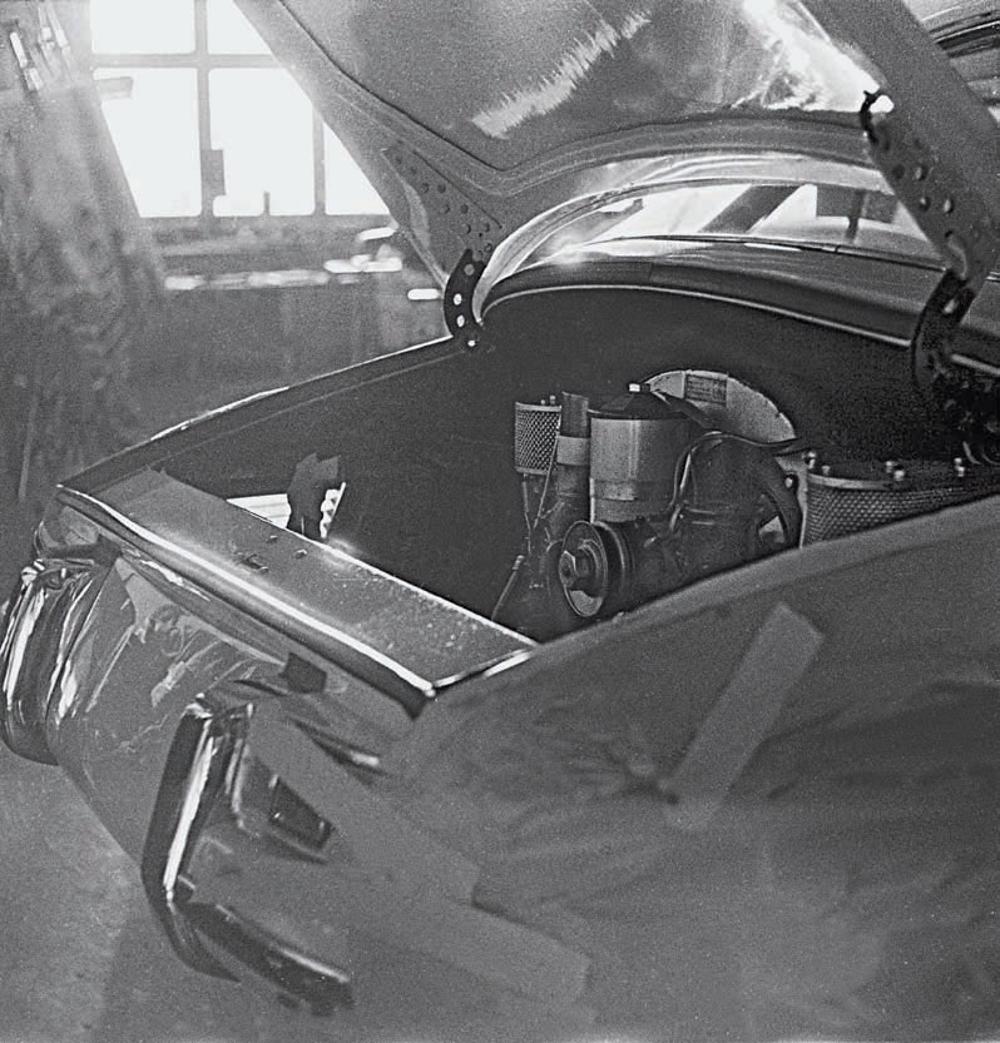

It remains one of the sweet ironies of unfinished formal educations that this particular dropout went on to supervise, direct, and influence the design of some of history’s most style-setting vehicles and significant products. That it proved to be no drawback apparently was a family legacy. While Ferry had taken evening courses in mathematics, physics, and engineering, the luxury of completing formal university education had eluded F. A., Ferry, and Ferdinand Porsche as well. Back in Zuffenhausen, F. A. entered the company’s apprentice program in early 1958. For his first nine months, he worked for engine chief Franz-Xaver Reimspiess for whom he drew all the pieces of the Typ 547 Carrera engine. “I had to memorize them,” he said. “The specifications of the screws, of the cylinder head, the cylinder itself, crankshaft, camshafts. All these things I had to recite and draw a profile of the Carrera engine. “I was then sent to the car body division to work with Mr. Komenda. Then I worked . . . on the lights from the 356C, the bumpers. . . . It was my father’s wish that I get to know the car body division and simply gather knowledge ‘from scratch’ with the people there and work together with them. I knew Mr. Komenda and Mr. Reimspiess from my childhood, dating back to Gmünd and the old Stuttgart days before the war,” F. A. continued. “I worked with Komenda. He was very strict. He naturally had formal views. So many areas were parts of that division; there was the electrical department that was part of Mr. Komenda’s division, and the car body department. The steering wheels and all the parts were manufactured there,” F. A. said. There were many times that F. A. heard, “No, no, that’s not the way it’s done.”

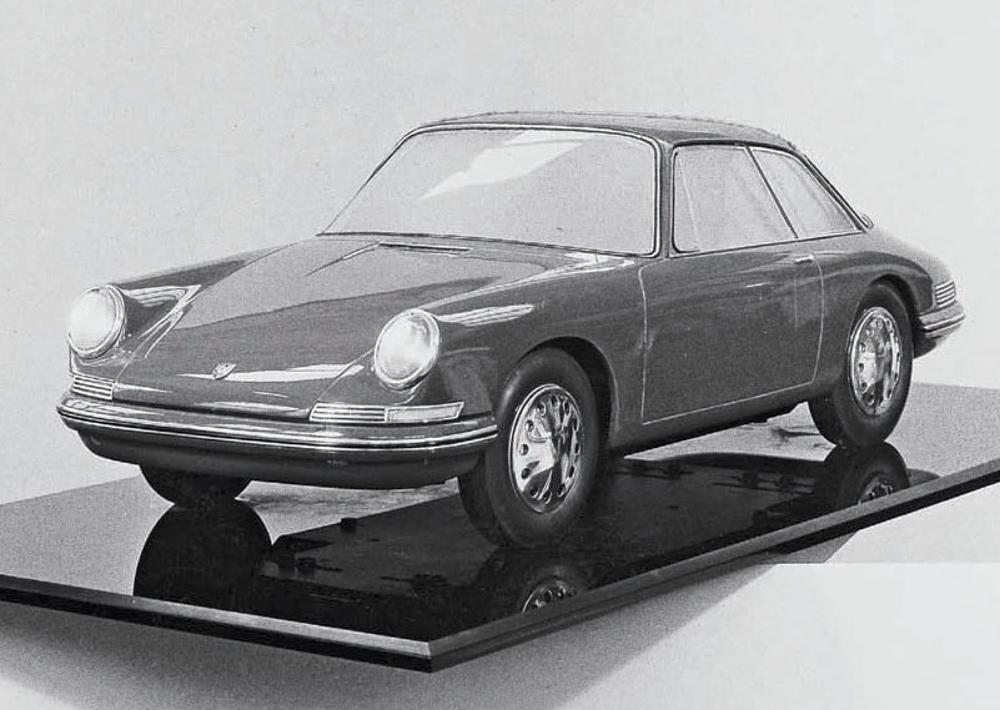

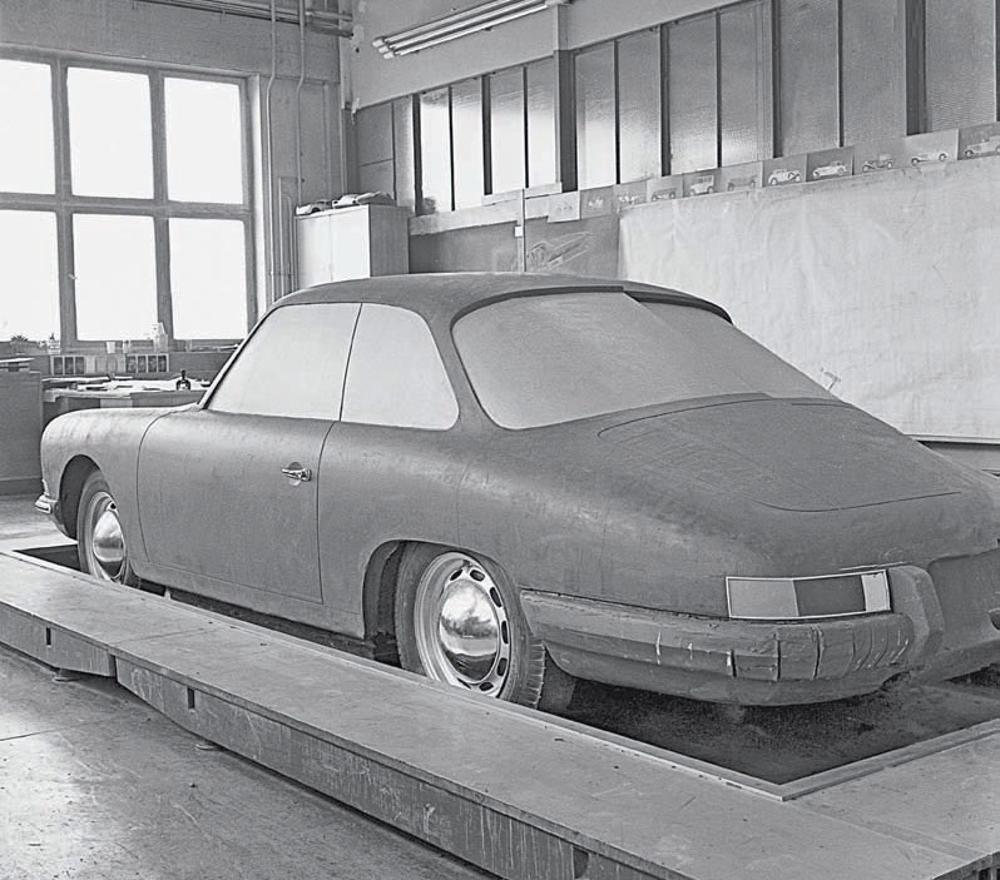

Komenda started him off in the racing division. “I was well acquainted with Mr. [Wilhelm] Hild and Mr. [Hubert] Mimler and the whole staff of the racing division,” F. A. recalled. As one of the seven people in Heinrich Klie’s design studio, F. A.’s first design assignments were to work on the Formula Two Typ 718/2 and then the first Formula One car, the Typ 787 planned for the 1960–1961 season. It was during this time, through 1958 and into 1959—not at Ulm—that his thoughts grew clearer. This was not an Introduction to Design or Fundamentals of Sculpture education he was getting. This was Ferry’s “Porsche Management 101” curriculum. F. A. sought ideas, insight, and learning wherever he could find it. Modeler Ernst Bolt told Tobias Aichele that, “Butzi wandered back and forth between the body department and the model department,” from Komenda’s workshop to Klie’s. As Aichele wrote in his history, Porsche 911: Forever Young, “Suggestions from the young designer were gladly incorporated, but overall responsibility for the Goertz-Porsche cooperative project remained with Heinrich Klie. The half-models were considerably closer to the later 911 silhouette than the first Goertz creations.” “ I was never convinced, that we must build a new Porsche just like the old one.” — F. A.

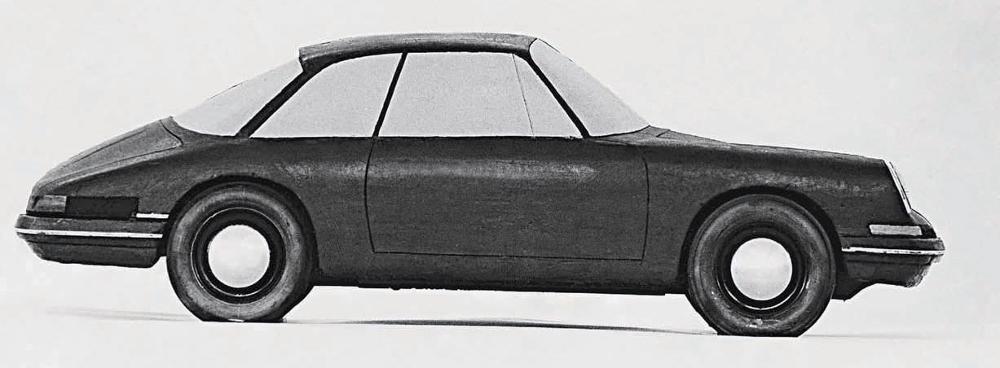

A pattern and operating procedures moved into place as well. Throughout F. A.’s youth, he had watched his father run the family business. Ferry was neither a graduate engineer, nor an artist, nor an accountant, nor a salesman. Yet he knew how to find those people, how to keep them challenged and satisfied, how to respect and appreciate them. He was perceptive and imaginative with the ability to influence a line, suggest a suspension alternative, discuss an engine configuration, or recommend financial terms for an international distributor. He became a jack-of-all-trades and a master of managing people. It was a skill, and it became the job his son emulated. Their family’s name was on the buildings and on the cars, and everyone who worked for Porsche understood they moved toward the same goal of producing the best automobiles possible for their customers as part of the growing Porsche family. Klie’s designers and modelers took significant elements from Goertz’s second efforts: First, they replicated the tubular front fenders that emerged from the low sweeping front deck lid, and they improved the fastback roofline that developed during the Goertz/Klie side-by-side collaboration. Second, at some point they realized that although Erwin Komenda continued to offer proposals for the next Porsche, they were developing the new Porsche. “I was never convinced,” F. A. explained in 1991, “that we must build a new Porsche just like the old one.” It remained a busy time at Porsche. At the end of 1958, the company discontinued the popular Speedster, replacing it with a more civilized Convertible D assembled up the road at Drauz Karosserie in Heilbronn. In the engineering department, Technical Program V (T5) entered its final development phase as the company prepared to replace its 356A series with the new B models for introduction at the Frankfurt auto show, the Internationale Automobil Ausstellung (IAA), in September 1959. In Zuffenhausen, construction laborers hurried to complete Werk III, the next phase in building expansion providing additional workspace.

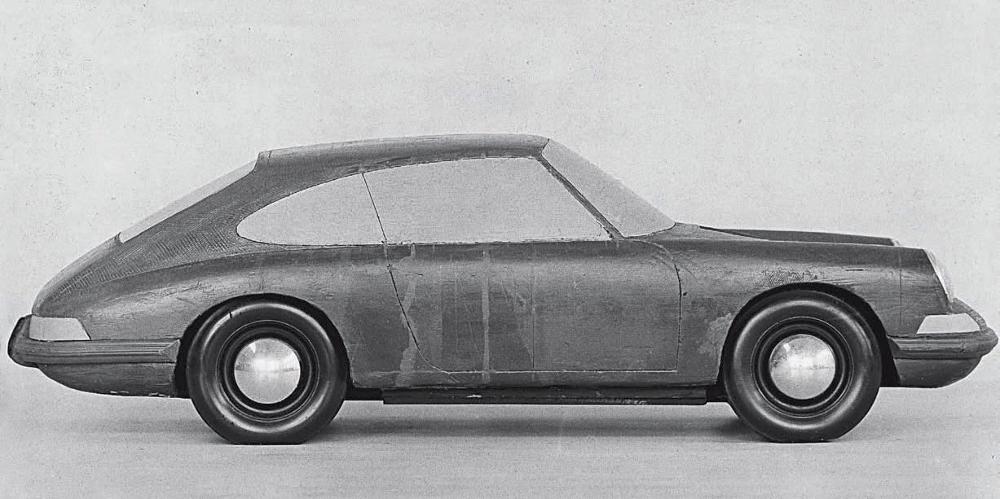

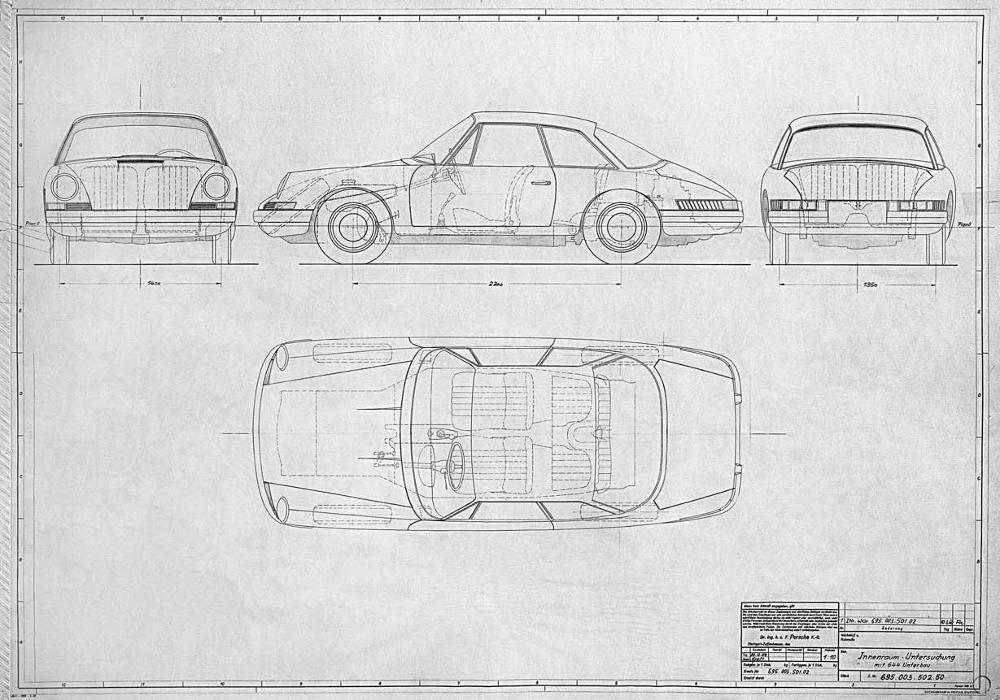

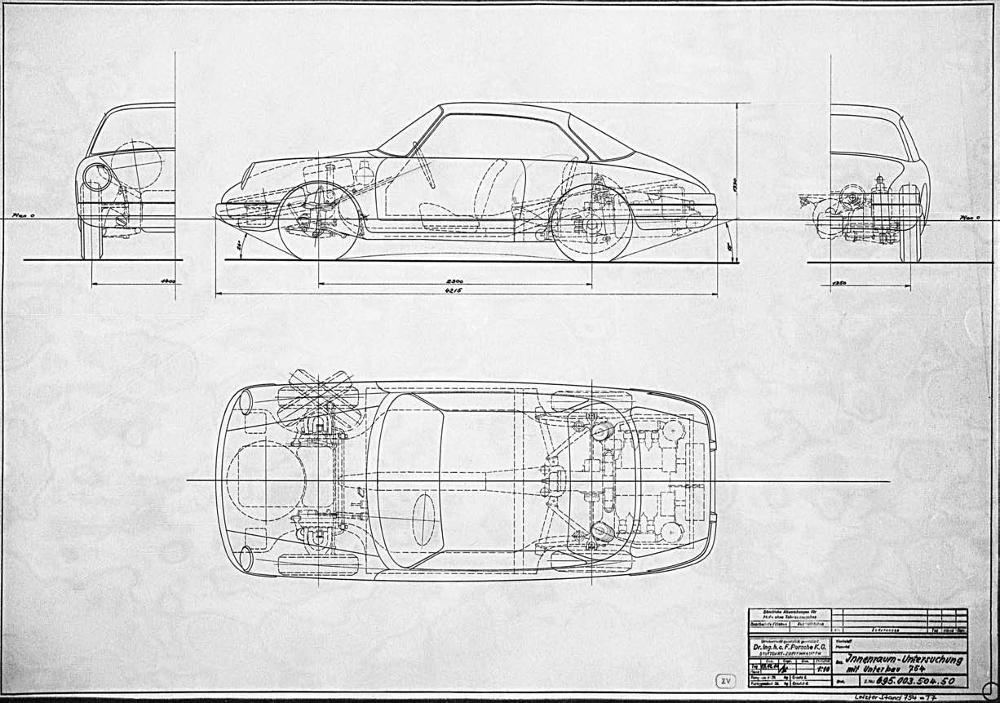

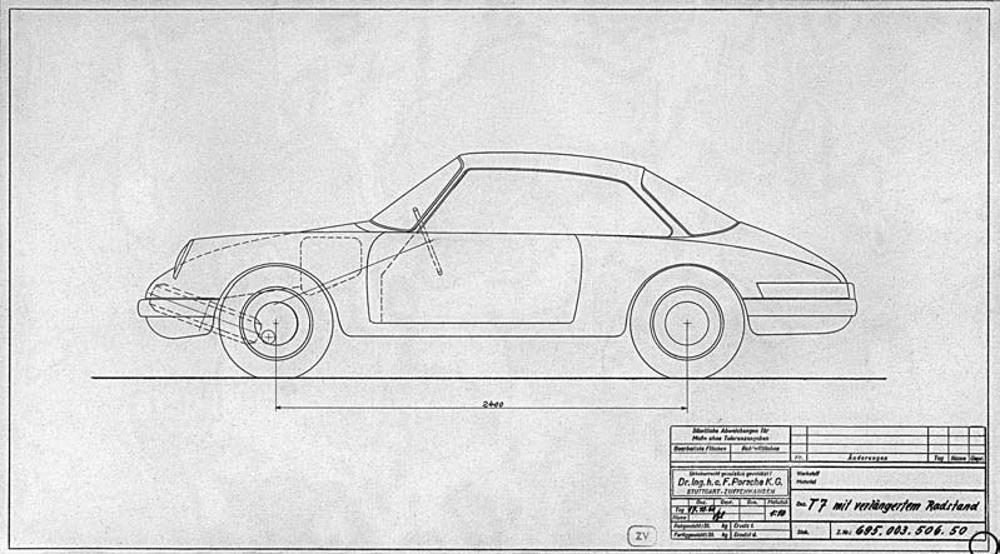

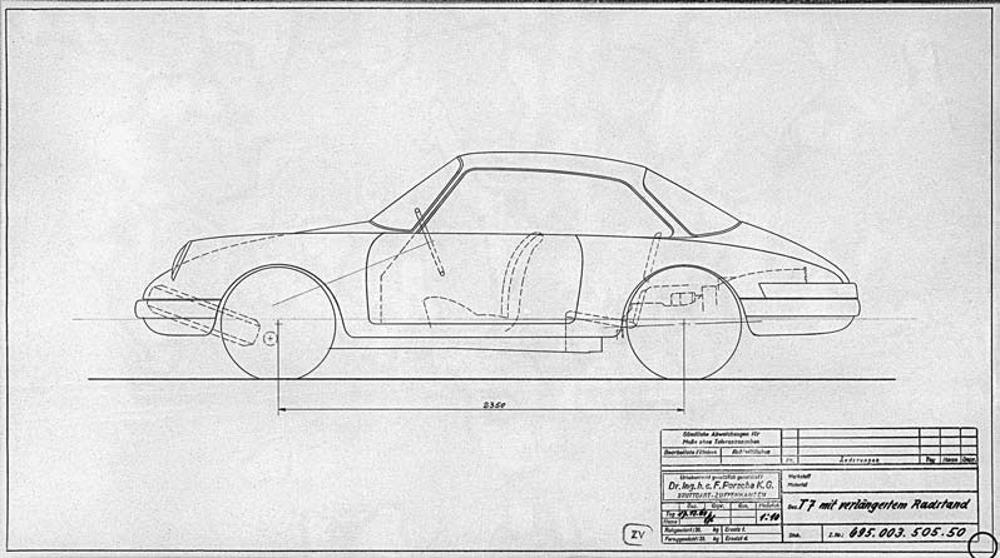

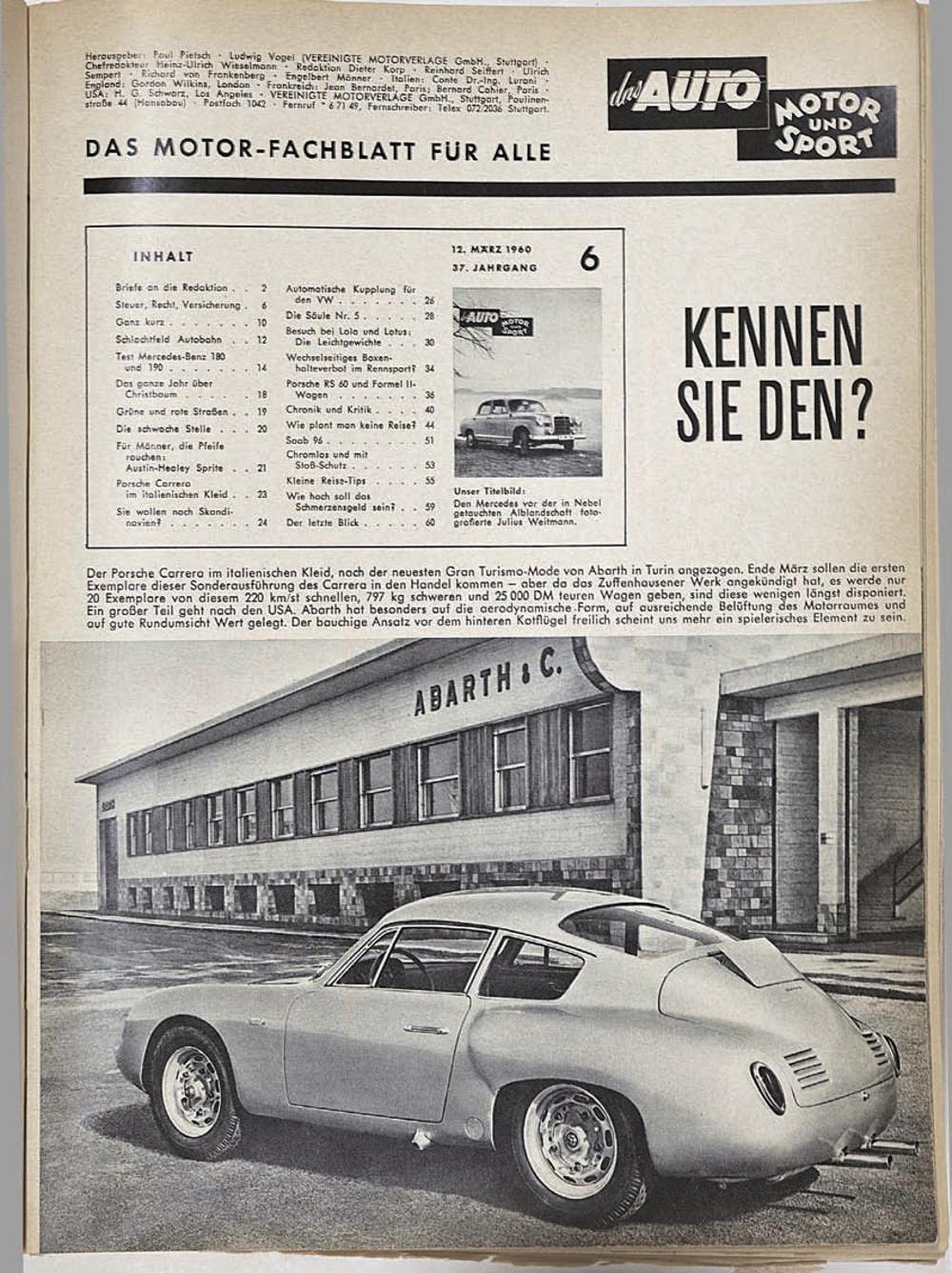

In an effort to fill out starting grids in Formula One and Two races, the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA) invited manufacturers with enclosed-wheel sports cars to enter. Porsche’s success in these races emboldened Ferry to enter the open-wheel fray. What’s more, a corollary to FIA regulations for the 1961/62 sports car season led Porsche to contact Carlo Abarth, an Austrian ex-patriot living in Italy. Abarth was an old friend of Ferry’s father from the 1930s. He had introduced Ferry to Piero Dusio and his Cisitalia in 1946. While visitors milled around the just-introduced 356B series cars at the Frankfurt show that September, Ferry and Franz Reimspiess met Abarth to discuss his manufacturing a lightweight racing coupe based on the 356B to take advantage of the rules loophole. Concept proposals from Komenda’s body engineers and Klie’s prolific model shop for the next Porsche appeared in front of Ferry like clockwork. Typ numbers ratcheted up as engineering innovations in chassis, wheelbase length, and suspensions encouraged new bodies. The 695 experiments gave way to the 754 series around the middle of 1959. Whatever development procedures Komenda’s staff may have followed, Klie’s designers had a smoothly polished routine. Designers Gerhard Schröder, Fritz Plaschka, and Konrad Bamberg were part of Klie’s studio and as F. A. explained, “Mr. Klie was there in those days. He was in charge of the studio.” They and three other men, Ernst Bolt, Hans Springmann, and Heinz Unger, worked together on scale models. Nicknamed the “Three Musketeers,” Bolt, Springmann, and Unger modeled car bodies in 1:7.5 scale and 1:10 scale. It was a painstaking and painful process that began with forming the models using Plasticine heated to between 120 degrees Fahrenheit and 140 degrees Fahrenheit (50 degrees to 60 degrees Centigrade) to soften it and keep it pliable. (Clay, Heinrich Klie’s medium of choice, was even less forgiving.) Blisters were common. F. A. contributed ideas to the Three Musketeers, often developed from his own hastily made sketches roughed onto paper or chalked onto a blackboard. Each of the models—no matter whose authorship—went to Ferry Porsche for his judgment. If it earned his approval, then Fritz Plaschka and Gerhard Schröder translated those into full-scale drawings.

Previous Page

Page 3

Next Page