Associated albums

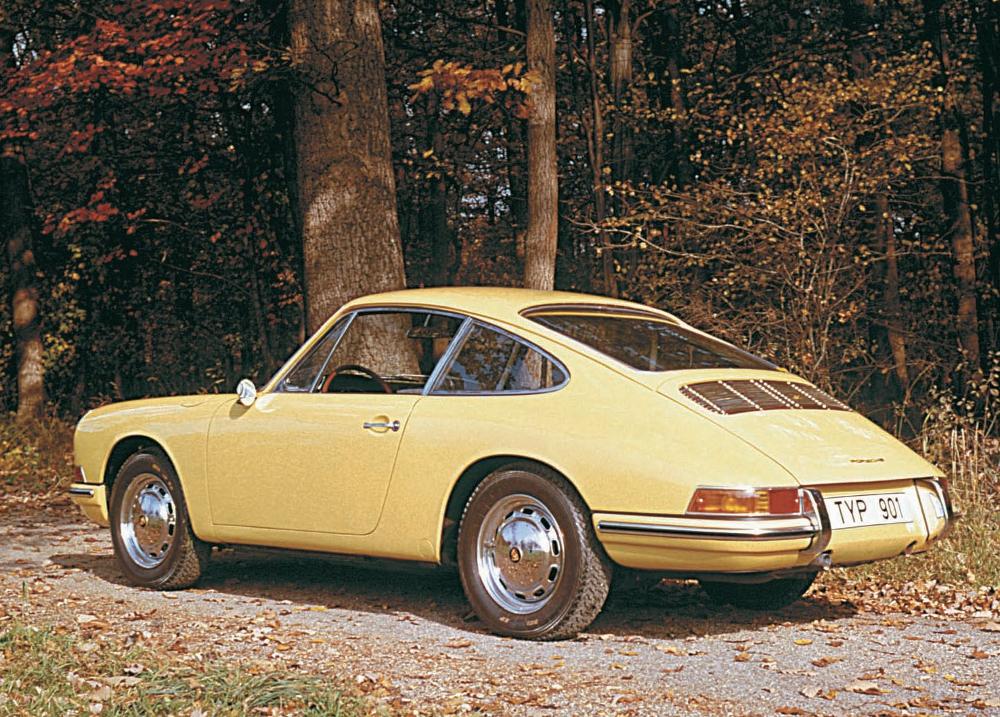

Klie’s model department delivered a bold and shining new concept to Ferry on October 9, a few weeks after the 1959 IAA show closed and one month after the chairman’s 50th birthday. It was designated the Typ 754 on the Technical Program VII chassis (or T7). The T6 designation belonged to the next generation of 356s that were due to reach customers in 1963. Proud of his team’s concept, Klie quickly had cast a resin model from their original and they finished it in blue paint. Ferry authorized a full-size model, and Plaschka and Schröder raced to complete it. On December 28, after viewing the 1:1 Plasticine representation, Porsche immediately authorized advancing the concept to the next phase, a see-through model. Crucially, as Aichele reported, Ferry Porsche “ordained that no feature of the 356 era should unconditionally be carried over to the new model.”

PORSCHE STYLING:AVERAGING THE ALPS Kolb explained the technique of making full-scale drawings of model concepts. They used a three-dimensional grid system to identify points on the model that they transferred to the wall-size sheets of paper. This proved an inexact method of upscaling a car model that measured roughly 400 millimeters long—not quite 16 inches—to a drawing stretching 4,100 millimeters or 13-plus feet long. Such large changes in scale guaranteed that “no matter how carefully you transferred the points,” Kolb said, “the roofline looked like the Alps. Picking which of the peaks or which of the valleys represented the real silhouette took special talent.” That talent belonged to Fritz Plaschka. Most designers at Porsche and elsewhere favored using vast French curve forms or sweeps. These were slender pieces of wood sanded smooth and trimmed in long gentle bends to help steady their hand in an arc across the long span of a fender curve or a descending roofline. Some of these were just thin strips that the designers could bend to meet the contour they had in mind. Komenda had a set that were his specifically and legendary in the minds of other designers, “the Komenda sweeps.” Plaschka, by contrast, made this roofline, his so-called big line, by hand. His steadiness formed the profile of the new Porsche.

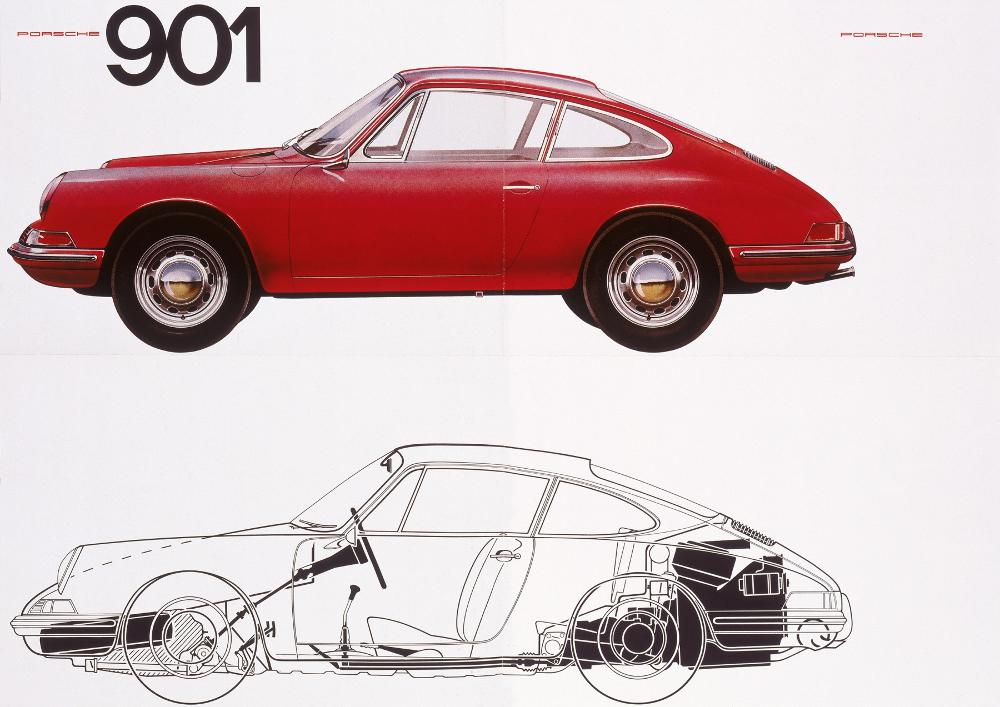

“The next step was to ‘industrialize’ it,” as Schröder explained. Before joining Porsche in 1954, he had worked with independent coachbuilders Ramseier & Cie, in Worblaufen, Switzerland, and Karmann in Osnabrück, Germany. At Karmann his first job was in “construction development,” where he established the body forms for Volkswagen’s Karmann Ghia coupes and convertibles prior to casting body stamping molds for production. These experiences gave him the knowledge and perspective to understand “if it was technically possible to build it,” as he put it. Working side by side with Eugen Kolb, the two men took Klie’s scale model and Plaschka’s 1:1 drawings, and from these, they made sectional diagrams by applying narrow black tape onto large paper to develop all the forms and contours of the automobile. Their task relied as much on interpretation and inspiration as it did adherence to the small-scale model. Along each step, there was design. Schröder, Kolb elaborated, regularly corrected and improved forms, shapes, and the overall appearance. “We always make this first line of the body. And then we [him, Plaschka, and Klie] asked Schröder, and we discussed this line. He had a perfect feeling for the shape.” The rapid pace of activity around Zuffenhausen continued into 1960. It grew so much that despite the new Werk III completed the previous September, Ferry sent finance manager Hans Kern and corporate secretary Ghislane Kaes on a mission to find land for a separate research and development facility. Expansion around the Zuffenhausen works was impossible with the land occupied by Reutter and other manufacturers. Klie and Porsche’s longtime aerodynamicist Josef Mickl took the blue-painted 1:7.5 scale model of the Typ 754 into Stuttgart University’s wind tunnel. The body required a few minor tweaks. Throughout this time, F. A. Porsche’s role underwent tweaking as well. As a design team member, he offered nudges and suggestions in their projects as they morphed from a three-dimensional miniature to two dimensions in life-size on paper and then onto the full-size Plasticine for final approval and first body molds. He changed the rear side windows from pointed ends on the 754 to the curve that became an element of the production car’s silhouette. He recessed the top of the rear window—not only to provide ventilation, but also to break up the large roof surface. The time Mickl and Klie spent in the wind tunnel located the optimum placement for that inset and this improved airflow over the car body. Prototype development and series introductions continued in Zuffenhausen. Few ideas were discarded. Komenda’s earlier Typ 530 notchback roofline entered production when Karmann began manufacturing the 356B Hardtop Coupe. The forms were nearly identical; Karmann’s workers began with a cabriolet body onto which they permanently welded the hardtop roof in place.

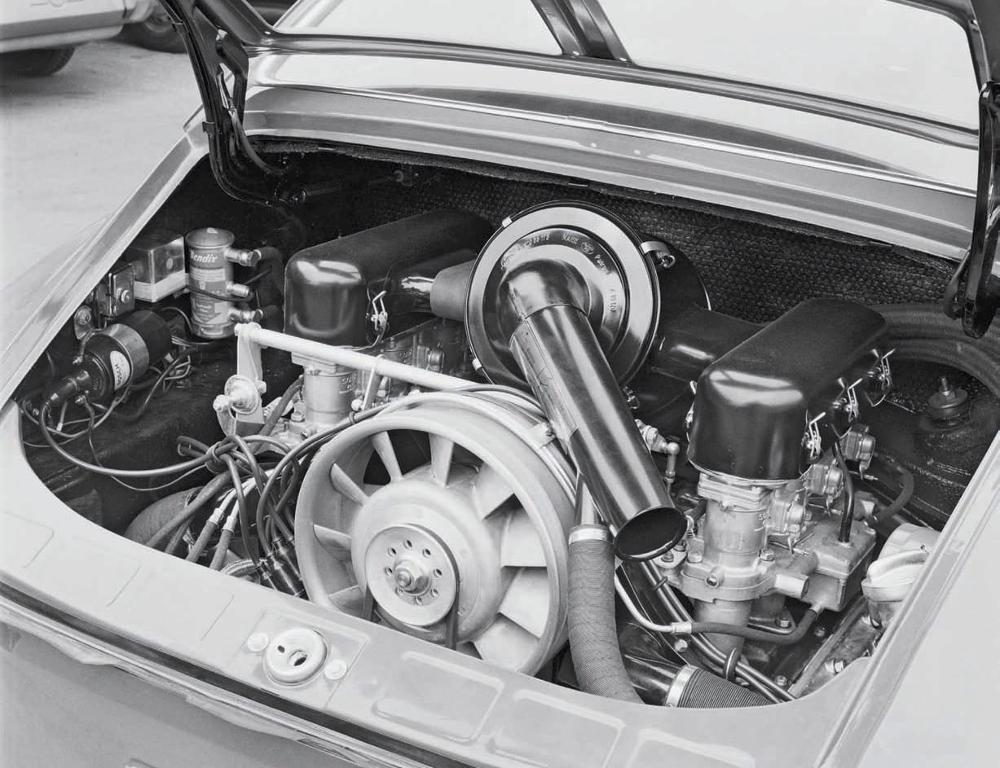

In February the first of Carlo Abarth’s 356B Carrera GT Lightweight coupes arrived from Turin. With a roof height compatible with shorter Italian technicians, few of Ferry’s taller team racers fit in. Wet weather testing soaked the drivers inside as much as the observers trackside. Ice formed in the foot wells of the Abarth Carreras that Porsche ran in the winter rallies. With Abarth subcontracting body manufacture to three Italian coachbuilders, it became clear to Ferry that not everyone could match the quality he demanded in car manufacture. Klie’s designers developed a new series on the shorter 2,100-millimeter Typ 644 chassis under Technical Program VIII, the so-called T8. They showed these to Ferry in March 1960 even as engineering work advanced on the T6 series 356B models for introduction in mid-1961. By yearend, The Three Musketeers along with Schröder, F. A., and the others offered yet another submission to F. A.’s father, this dubbed the Typ 695 T7, designed on a 2,375-millimeter wheelbase. Investigating how passengers and the rear-mounted engine fit inside the bodywork was a recurring theme in their efforts. On December 2, 1960, Hans Kern met Ferry to look at a piece of property midway between Weissach and Flacht, some 25 kilometers from Zuffenhausen. It was more than three times the area Porsche had wanted. In a moment of lucid foresight, however, he moved ahead on the purchase. Who influenced the appearance of the car was one question Ferry had to resolve during its transition from Komenda’s next Porsche to Klie’s new Porsche. Issues of another kind of power proved equally vexing: what sort of engine was to drive this new car? Almost as soon as Ferry concluded it was time for the new Porsche, he had performance targets in mind. He enjoyed the acceleration of the two-liter Carrera engine, but he was less fond of its noise and its complexity. If this were to be the basic engine for the car, “it should be quiet,” he told Tobias Aichele, “not as noisy as a race car.” To reach Ferry’s target of 130 horsepower, his engineers calculated they needed a minimum two-liter displacement. Ferry required no loyalty to four-cylinder configurations: That was then; this is new. Engine designer Hans Mezger already had developed the opposed one-point-five liter eight-cylinder Typ 753 engines for the 1962 season Formula 1 car, the Typ 804. The Typ 718 W-RS Grossmutter sports racing car ran on two-liter flat-eight Typ 771 engines. These were pure racing powerplants, loud and volatile, with narrow power bands of explosive performance and fantastic complexity; it took trained mechanics 220 hours—27 and a half workdays of eight hours—to rebuild a single 771. That was enough of a challenge for a racing effort; it was inconceivable for a series production car. “It should be quiet, not as noisy as a race car.” —Ferry Porsche

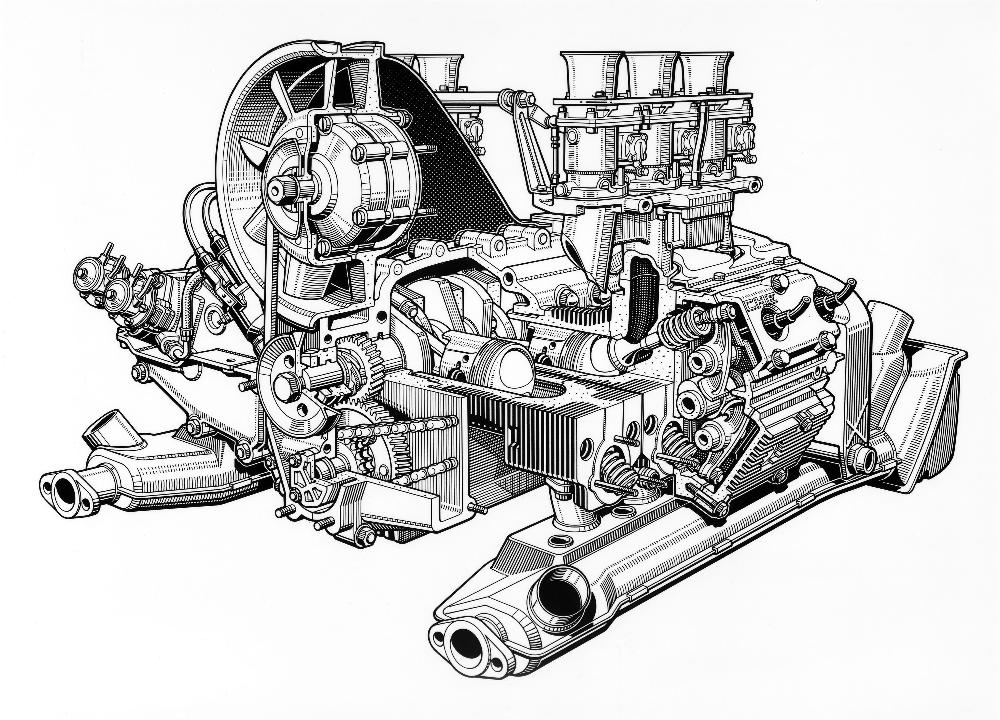

Porsche, the company, had lost engine designer Ernst Fuhrmann when Ferry promoted newcomer Klaus von Rücker over him to be chief engineer. Von Rücker joined the company in November 1955 after several years at Studebaker, the American car manufacturer in Indiana that had hired Porsche engineering in 1952 to develop a sedan (the Typ 542) for them. When Porsche, the engineering service, completed the project, Ferry hired von Rücker to gain his intimate knowledge of American engineering and manufacturing capabilities and automotive tastes. Von Rücker appointed engineer Leopold Jäntsche to head new engine development. Jäntsche arrived from a similar position at Tatra, the Czechoslovakian carmaker who, in 1955, introduced its Model 603 with a 2,545cc air-cooled V-8 engine. For the road, the 603 developed 95 horsepower, but in racing tune, Jäntsche and his team had reached 175 horsepower on dynamometer tests. The engine utilized a pair of axial fans, one for each bank, as well as tubular oil coolers for engine temperature management. This soon became familiar technology to the engineers at Porsche. Jäntsche and his assistant Robert Binder developed an engine designated the Typ 745. It displaced two liters and used pushrod-activated valves. Unsurprisingly, a small fan cooled each bank of three cylinders. Two camshafts—a legacy of Ernst Fuhrmann’s Typ 547 Carrera motor but not used the same way—operated intake valves (by one camshaft fitted above the crankshaft) and exhaust (by the other one below.) Three-barrel side-draft carburetors fed fuel into each cylinder bank through the valley between the valves; this established the engine’s dimensions. As Aichele pointed out in his book, Porsche 911: Engine History & Development, this configuration “permitted a low engine profile, with the added advantage that each cylinder bank had its own cooling system. The low height implied that the Type 745 would be a so-called ‘under-floor motor,’ that is, the engine would not be much taller than the transmission. . . . This concept is usually reserved for commercial vehicles.” One proposal that Ferry reviewed did show the engine under the rear seats. It’s a safe bet that he had other configurations in mind as well.

Early engine tests showed that the pushrods limited engine speed. Horsepower output never exceeded 120 at 6,500 rpm. Jäntsche and Binder enlarged cylinder bore from 80 millimeters to 84 millimeters to reach 2,195cc displacement. They reached their goal of 130 horsepower. Ferry, whose hope never flagged—witness his willingness to expend further development funds and personnel to Goertz’s body designs—ordered a prototype 745 engine installed in the 754 T7 body. One night early in November 1960, Helmuth Bott took the new car out for a test run. His postmortem was devastating: “Das können wir vergessen” (We have to forget about it), he wrote. Bott had little problem with the body, suspension, or its handling. “It is as loud as a threshing machine,” he explained in his report. In the best of the tradition of an engineering firm that loved nicknaming its successes and its failures, the “threshing machine” stuck. The busy clatter of the pushrods and the howl of the twin fans helped doom the engine. More significantly, racing engineers vetoed the design because it required displacement increases, not simply higher engine speeds, to elevate horsepower to competitive levels. This situation literally sent engineers back to their drawing boards. In early spring 1961, Porsche introduced the Karman-built/Komenda-designed 356B hardtop coupe and six months later, the company replaced the T5 engineering series with 356B T6 body and chassis improvements. Through the summer, Klie’s model department pressed ahead with open-wheel plans for racing. The seven-man team worked rapidly on the slim 804 body for Formula One for 1961–1962. Then on October 16, Ferry climbed on a bulldozer and broke ground on the new testing, research, and development center near Weissach. The first thing on his engineers’ agendas was a proper skid pad—190 meters in diameter—for chassis, suspension, and tire testing. Outside the confines of Werk I, II, and III, Ferry’s racing efforts met success with the new lightweight Abarth-bodied 356B Carreras. But the workmanship from Italian subcontractors had forced extra work hours on Porsche’s racing mechanics and body technicians before a single customer took delivery—and many of the Abarth GTLs returned with “warranty” complaints not from Porsche drivetrains or chassis but from the ill-fitting body panels. For Ferry, as the 52-year-old chairman of a multivehicle manufacturing concern that shipped road-going and racing cars to customers and events around the world, the challenges were endless. Testing revealed the new, highly technological flat-eight Typ 804 grand prix engine still was down on power compared with its competition. This was a development hurdle that could not be cleared. In road racing, the FIA changed the rules for Grand Touring cars once again, affecting those who planned to compete in 1962. Carlo Abarth warned Porsche he wanted to upgrade one of his cars into a class that raced directly against the lightweight coupe he had done for Ferry. Porsche’s body engineer continued undermining design efforts that, in some cases, came from Ferry’s own son. It came to a head at a design review that Ferry Porsche scheduled for mid- October 1961. According to Kolb and Schröder, Ferry had made clear since mid-1958, seeing Klie’s half-model mounted against Goertz’s second proposal, that he preferred a fastback roofline with a 2+2 seating arrangement that both of these concepts showed, one that incorporated shorter rear seats for occasional or emergency use. Kolb was there for this next review. He recalled that the full-size drawing for the Typ 754 T7 with Plaschka’s long sloping roof and rear window representing Klie’s group was on a large board, as was one for Komenda’s latest notchback four-seater. “There was a big meeting at Werk I about the rear seats,” Kolb said. “Ferry, Komenda, Schröder, Butzi, they were all there. The designs for both versions of the car were on frames away from the wall. It was usual at Porsche to have two cars developed, parallel versions. It was quite normal. And then Komenda measured the rear seats of the other car [the Schröder development drawing] and wrote new measurements for the rear seats—as everyone was looking. Then Komenda said, ‘How do you choose now? This or this?’ “Komenda, Ferry, and others discussed the shapes of the rear seats. More comfortable, Komenda wanted to do. And Butzi was clear: More sporty, less comfortable. “Ferry recognized the problems between these two guys and the bodies. And then Ferry said, ‘We make this,’ and it was the Butzi version. In front of all the people, Komenda was in second place.” That day advanced the 2+2 to full-size preparation. And, it turns out, this is when Ferry’s— and his son’s—relationship with Erwin Komenda began to deteriorate. “ Komenda, Ferry, and others discussed the shapes of the rear seats. More comfortable, Komenda wanted to do. And Butzi was clear: More sporty, less comfortable.” — Eugen Kolb

Previous Page

Page 4

Next Page