Associated albums

About this time, Ferry replaced von Rücker as chief engineer with Hans Tomala, already involved with the new car, but now given engineering development along with his other responsibilities of design and manufacturing. Ferry had good reason; he had driven the T7 body with the twin-fan 745 engine for several months before, and as Aichele put it, he “banned the design of other new pushrod engines once and for all.” That meant only overhead cams would do. And this required pulling racing engine designer Hans Mezger into production work. The rapidly escalating costs of the new Porsche’s development convinced Ferry that continuing in Formula One (especially after so little success) was not a prudent investment. He canceled the 804 program for 1963. His competition engine designers suddenly were available, a decision that made sense because there was never a doubt that the company and its customers would race the new production car. Mezger knew the performance capabilities that dual overhead camshafts provided from his work on the 771 and 804 racing engines. He never considered anything else for the new production powerplant. He also understood that gear-driven overhead cams were fine for racing where costs, intricacy, and noise were barely considered. Those were drawbacks for a road car, however. Mezger and fellow engineer Horst Marchart (who went on to head engineering research and development) developed a chain-driven overhead cam configuration that worked because of a hydraulic tensioner Marchart invented.

An engine’s ability to rotate fast relied on crankshaft stability. The 745 had four crankshaft main bearings, which seemed a logical configuration. But Mezger and Marchart wanted one on either side of each connecting rod. As the design progressed, this new engine carried the Typ 821 designation. At first they thought seven bearings would anchor the rapidly turning crank; however, they concluded by June 1, 1963, that they needed eight. In Karl Rabe’s record books, this engine went in as the Typ 901/1. Extreme testing showed problems with oil transfer to outer cylinder banks in hard cornering, presenting another serious drawback for racing applications. By this time, Ferry Porsche’s nephew, Ferdinand Piëch, had joined the company fresh from engineering school at the Swiss Technical Institute in Zurich. Like his cousin F. A. Porsche, Piëch had spent weeks before and after school sessions in the design department; by April 1963, he was a full-time Porsche engineer. Combining the lessons learned from his grandfather Ferdinand Porsche and those he absorbed in Zurich, he pushed for the highest-quality materials from suppliers and matching work from his colleagues. As he was a Porsche family member, despite the protests of his uncle’s cost-conscious purchasing department, Piëch’s preferences generally prevailed. Ferry followed his recommendation to adopt dry-sump lubrication for the new engine. This system required a separate tank, lines, and pumps, but it ensured even oil distribution throughout the engine range and at any cornering force. In addition, the dry-sump system eliminated the need for a deep oil pan, lowering the engine in the chassis to improve handling. Still, with its vertical 11-vane cooling fan and downdraft carburetors above the engine, it sat too tall for some purposes.

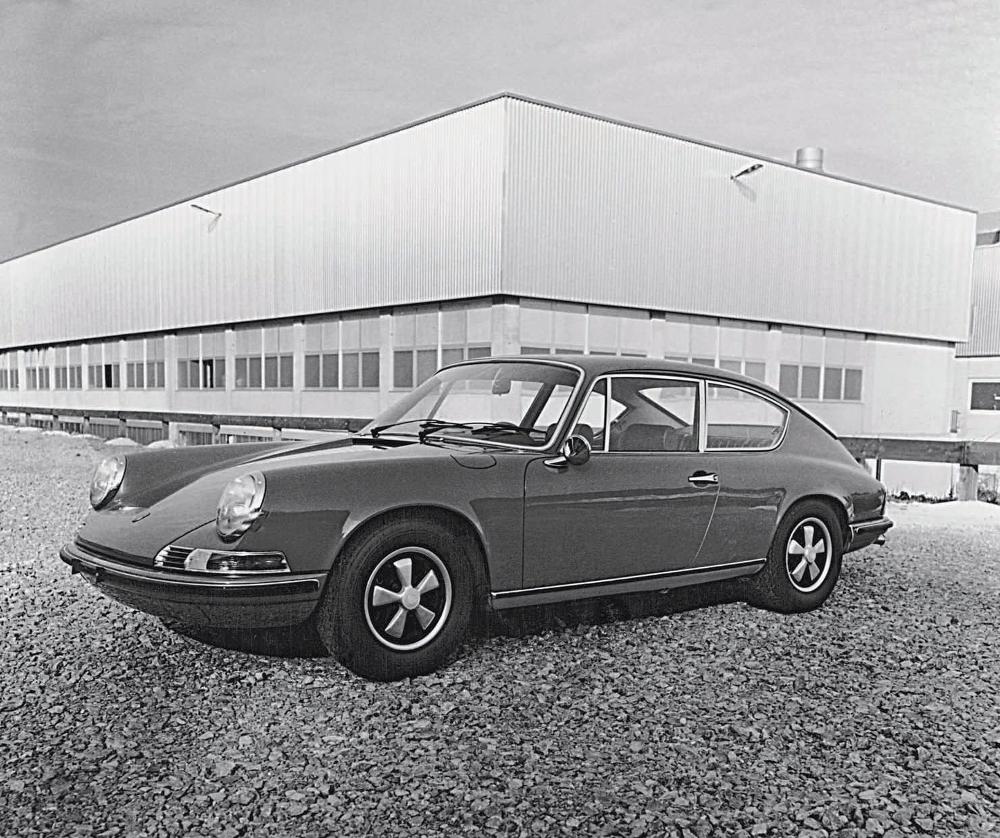

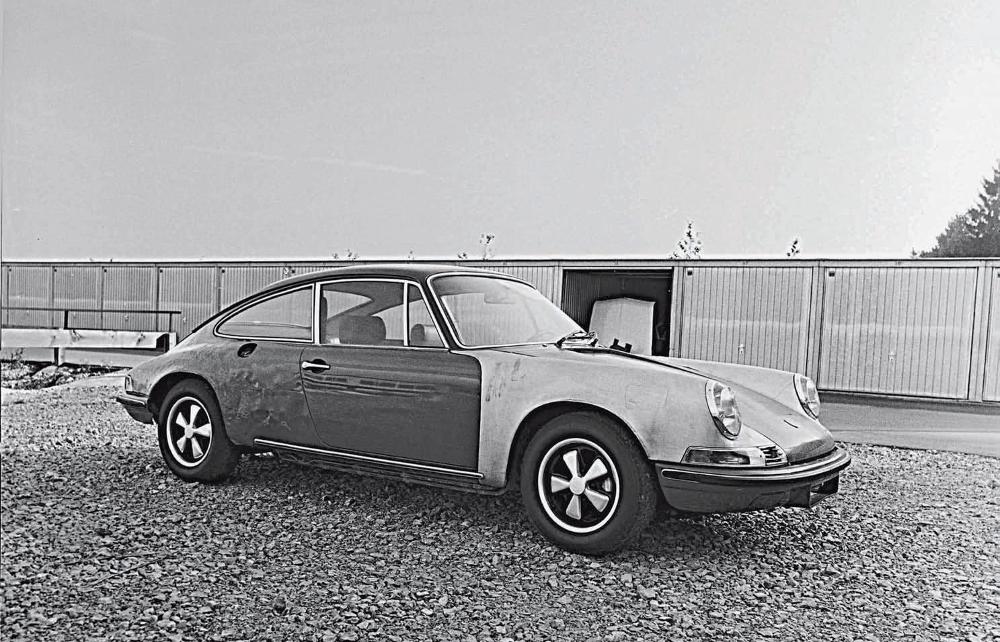

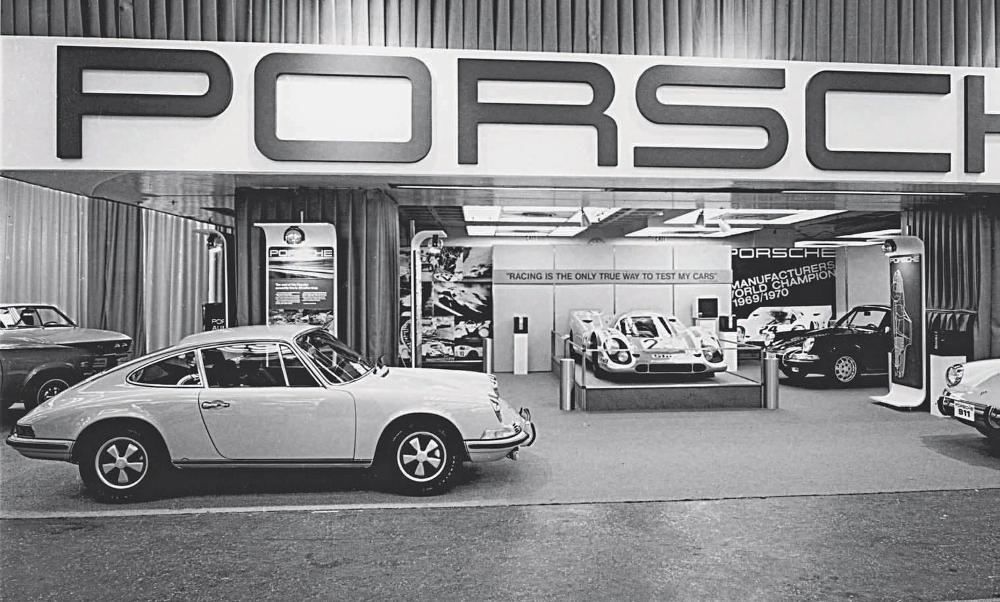

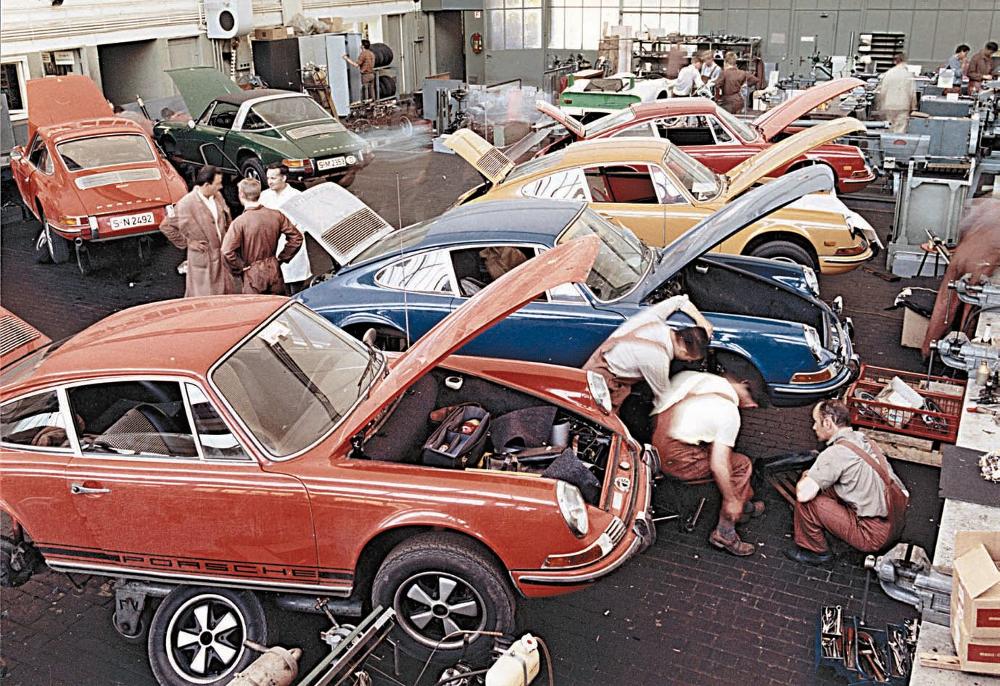

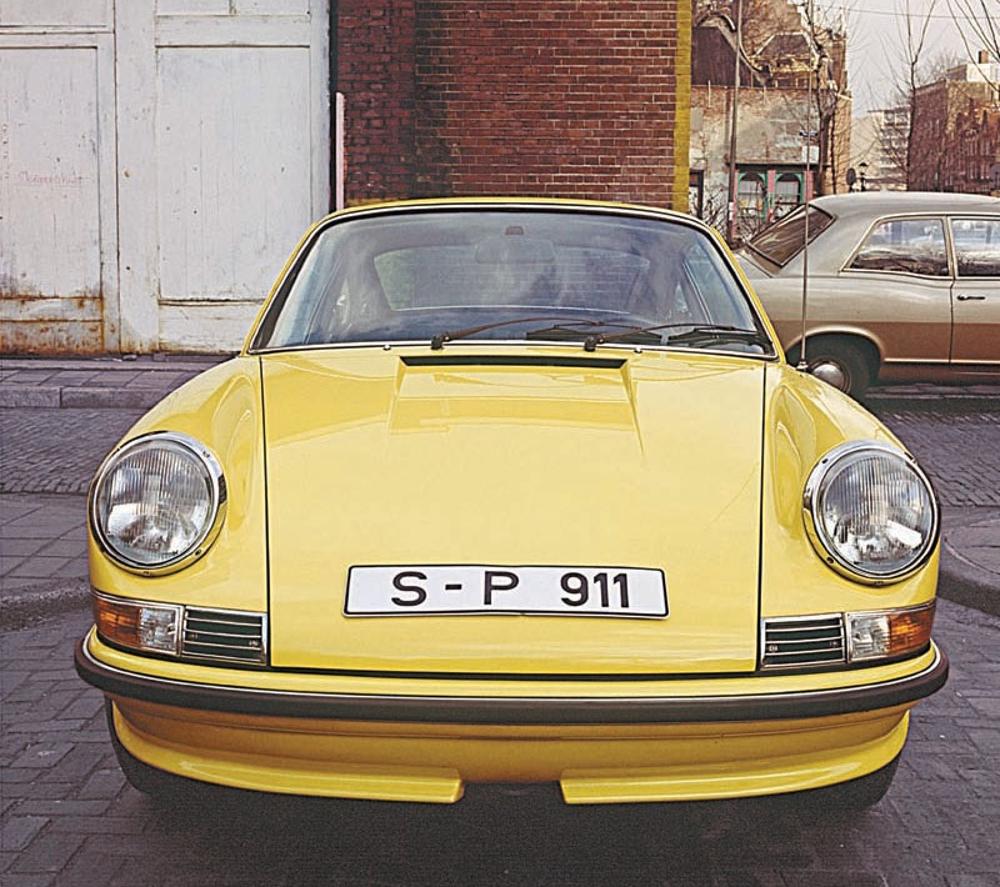

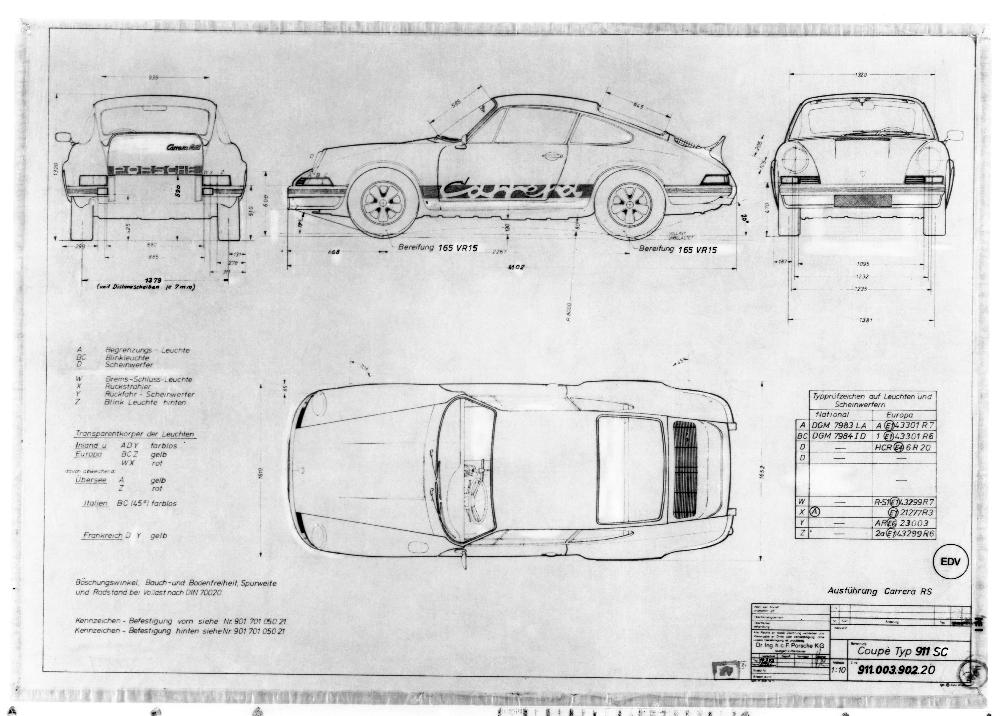

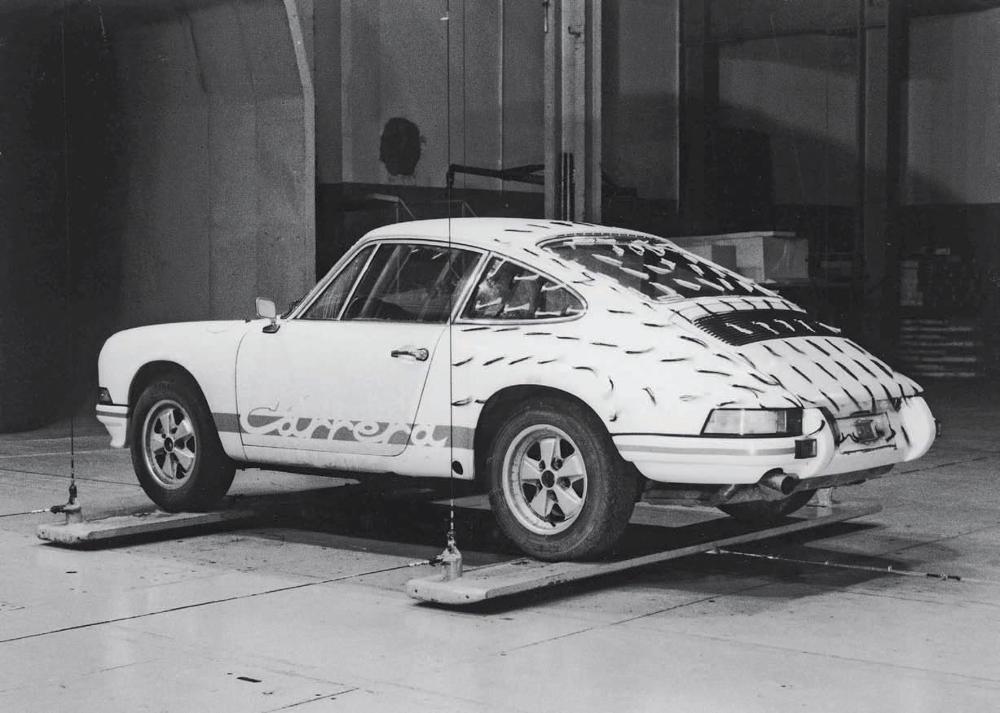

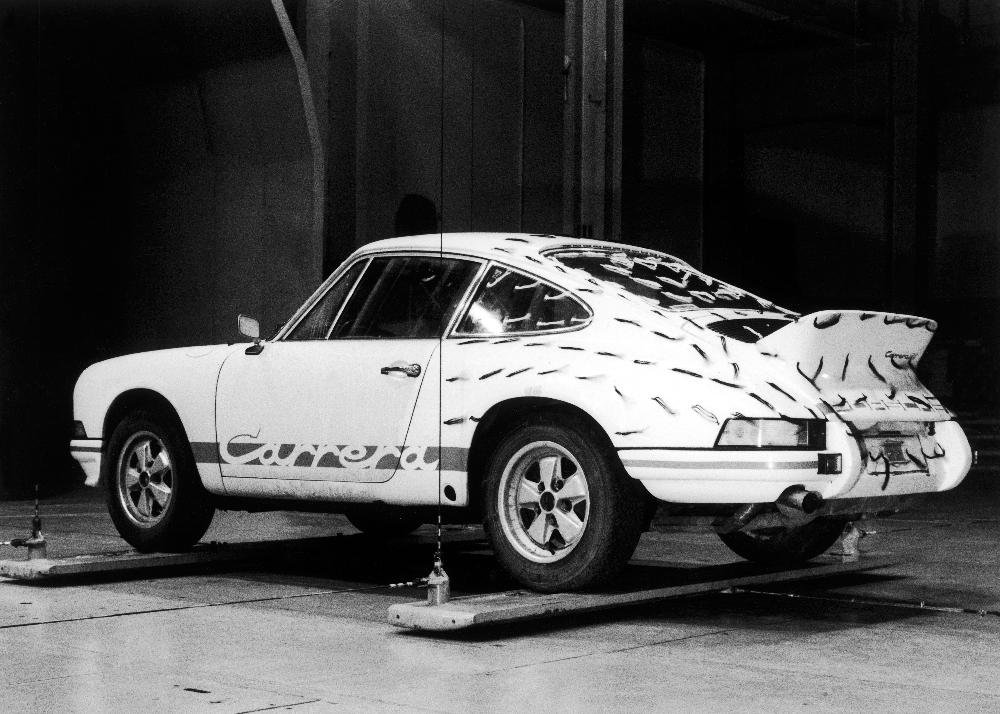

The Typ 901 designation—for the new eight-bearing four-cam engine and the complete car— first appeared in Porsche’s internal documents on January 9, 1963. The engine developed 130 net horsepower using DIN (Deutsches Institut für Normung) standards and 148 gross, according to SAE (Society of Automotive Engineers) calculations. Adding the dry sump did not necessitate a major Typ number change. By October 30, according to Aichele, engineers inside the company knew that Typ 901 engines “intended for production will be numbered sequentially beginning with the number 900 001.” That memo stated that engineering had reserved the first 100 engines for its own testing purposes. As Aichele learned, “The 901 prototypes were based on so-called replacement bodies, with chassis numbers beginning with the number thirteen. The first 901 development car,” he reported, “carried chassis number 13 321. Engineering numbered these forerunners sequentially only up to the tenth car. The eleventh, numbered 13 352, fell out of the sequence. The twelfth test car, numbered 300 001, bore the first production serial number.” Activity in Zuffenhausen was frenetic. Helmut Rombold’s rack-and-pinion steering system went onto the new car. ATE disc brakes, introduced on the contemporary 356C and SC models, came over as well. New independent front and rear suspensions improved handling and provided greater space within the 901 body. The nomenclature emerged from a worldwide parts-distribution and sales pact between Volkswagen and Porsche. The only available sequence of numbers that was large enough to handle a new Porsche model began with 900. Porsche’s neighbor Reutter, having helped in development of the new 2+2, balked at the expense of producing new tooling to manufacture the body panels and constructing new facilities to assemble the cars. Company founder Wilhelm Reutter had died in 1939 and his son Albert, who ran it after that, died in wartime bombing in Stuttgart. Walter Beierbach had managed the company successfully, but, when the family faced the financial commitment to produce Porsche’s new car, they chose instead to put the company up for sale. Ferry had no choice; Reutter had helped develop the new car and they knew too much about Porsche’s business. He invested six million Deutschmarks (DM)—nearly $1.5 million at the time, more than $11.4 million today—to acquire Reutter Karosserie. The new Porsche improved on the 356 in many ways. Fritz Plaschka’s “big line” roof provided 58 percent greater window glass area. The wheelbase, stretched only 100 millimeters (3.9 inches) from the 356’s 2,100 millimeters, and better but more-compact suspensions provided nearly twice the interior and front luggage capacity. Ferry’s aerodynamicist Josef Mickl reduced the coefficient of drag from 0.398 for 356 models to 0.38 for the new car. Running prototypes finally appeared on the roads around Zuffenhausen in March and April 1963. Ferry’s investment in the new car was approaching 21 million DM (more than $5.25 million at the time and nearly $40 million in today’s dollars), including the Reutter acquisition. It presented a staggering risk. Ferry debuted the 901 at the IAA international automobile exhibition in Frankfurt in September 1963. The car provoked enormous interest. The IAA opened in Frankfurt on Friday, September 13, 1963. Journalists got in as early as Tuesday evening, the 10th, and briefings introduced new cars to writers and photographers through Thursday. Auto show records reveal that 21 manufacturers debuted models during the 1963 exhibition. Mercedes-Benz showed the closest competitor to Porsche’s new car with its 230SL. Further out the engineering spectrum, both Rover Cars of Britain and NSU of Neckarsulm introduced startling new powerplants: Rover showed off a gasoline turbine and NSU displayed its first production Wankel rotary-engine models. Autos alternated with trucks at Frankfurt, the commercial vehicles filling the hall in even-numbered years while the odds went to automakers. In hall 1A, at stand 27, Porsche had rented 211 square meters, about 2,265 square feet out of the entire show’s 800,000 square feet. Surrounded by an Emailblau 356C cabriolet, a Togobraun SC coupe, and a Signalrot Carrera 2 coupe, the company introduced the 901, displaying its fifth prototype, No. 13 325, in a special blue paint. It was reported to be Ferdinand Piëch’s test car. Attendance records indicate that more than 800,000 visitors wandered the Frankfurt show halls over the next ten days. Porsche sales director for Germany, Harald Wagner, knew that delivery of the first production model was a year away. He encouraged his staff to make that delay clear. Despite this and its respectable price of 23,900 Deutschmarks ($6,020 at the time; about $45,000 with inflation at the end of 2012), and the fact that no drivable models existed for road tests, Porsche banked some sales deposits for the new car. (The price fluctuated between Frankfurt and the end of the year as specifications and standard equipment evolved.) This called for 7,000 DM ($1,755) up front, and it came with a promise that Mr. Wagner’s staff would send a letter notifying the buyer when they could pick up their new car. At the same time, nearly 400 loyalists placed orders for 356 models.

VON HANSTEIN’S ADVENTUROUS PROMOTION It hadn’t hurt Porsche’s cause at all that the company’s charming and shrewd press and racing director Huschke von Hanstein had stirred the waters in advance of the introduction of the 901. Von Hanstein was a regular reader of Auto Motor und Sport, the Stuttgartpublished enthusiast magazine circulated throughout Germany. Early in 1963, he saw photos published on the contents page that showed a new Mercedes-Benz 600 Series model testing on public roads. It generated a great deal of attention. Helmuth Bott’s engineers had created camouflaged versions of the 901 for nighttime testing, and Von Hanstein and Bott arranged for one car— nicknamed der Fledermaus (the bat) because of its two finlike wings on the rear deck—to be captured on film by a friendly photographer. Porsche Archiv director Dieter Landenberger explained that Von Hanstein himself delivered the prints to the magazine, along with the kind of information about the prototype that no spy photographer could know. Alongside the headline Abenteuerlich, the German word for adventurous, or even bizarre, a series of photos credited to Blumentritt in the July 27, 1963, issue whetted the appetites of Germany’s enthusiasts.

While only Helmuth Bott’s test drivers had accumulated any time in the new cars, the enthusiast magazines praised the 901 based on its appearance and specifications. Buoyed by positive feedback, Ferry prepared for the Paris Auto Salon, from October 1 through 11, a month later. He felt some relief at last. He still had millions of Deutschmarks to earn back, but internal battles over body style and the questions of usable engines were settled. Conflicts seemed a thing of the past. The French were loyal customers. He anticipated a good reception. There, visitors and journalists loved the car. However, the reaction from a fellow manufacturer was decidedly less warm. Automobiles Peugeot had registered with the French office of copyrights and patents the right to designate their models with a three-digit number that placed a zero in the middle. The first such use came with their Model 201 in 1929. By 1963, the sequence had gone as far as 403, 404, and 601. During the Paris show, Peugeot notified Porsche that it could not call the new car a 901 in France. Huschke von Hanstein, still in Paris, sent an urgent note to Ferry on October 10. France was a good market for Porsche cars. Ferry felt there was little use in reminding Peugeot that his 804 Formula One car had won at Reims the year before. In a rush of memos between Ferry, von Hanstein, and Wolfgang Raether, they contemplated renaming the car the 901 G.T. That idea died when it became clear there was no room to insert the two letters into materials ready for printing in German and French. On the other hand, with the three-digit Typ number appearing throughout any text material, changing the middle was relatively easy prior to mass printing.

On receiving Peugeot’s letter, Ferry halted production of brochures and the cars. Rather than antagonize an entire nation, he made his decision on October 13 to renumber the car as the 911 for all its markets effective November 10. Porsche had begun 901 manufacture on September 14, interrupted it on October 10 as they dealt with Peugeot and awaited their response, and then resumed around November 9. By this time, barely a dozen cars were complete. One went to Franz Ploch and Werner Trenkler for a cabriolet experiment and then on to Karmann; two cars—300014 and 300016—went to Paris distributor SonAuto for the Paris show, one for display and the other for demonstration, departing Zuffenhausen three days before the show opened. Porsche shipped another to Japan (300022) for an exhibition and still another to California (300012) for an automobile display near San Francisco. Perhaps only one or two cars slipped out to early customers in late September. The rest of them simply got rebadged as 911 models. The process to create the new Porsche had taken up more than a fifth of Ferry Porsche’s life. He turned 55 on September 9, five days before 901 production commenced. During that time, he directed his company through three evolutions in his 356 series, and he had worked with outsiders successfully—Drauz, Karmann, D’Ieteren Frères—and others less so. His racing programs evolved from the 550 Spyder through the 718 open and closed cars, and in and out of Formula One. It’s likely that Ferry truly believed his statement about the “shoemaker, stick to your last.” It held true for racing; while the Abarth GTLs were not perfect cars, they won races, and their successors, the 2000 Carrera GS Dreikantscheibers and the conquering 904s, proved that Porsche is the roadracing company. It was a highly eventful period of time, including the costly and unexpected acquisition of a neighbor he had hoped would simply remain a partner. The roots of the first 356s clearly were engineering and technology derived from the Volkswagen. Through their own era, they evolved into vehicles purely Porsche. The 911, and its entry-level sibling, the four-cylinder 912, drew not only a line in the sand, but also etched a demarcation point in automotive history books. These cars began as Porsches, supervised in design, engineering, and manufacturing by F. Porsche and F. Porsche Jr. In some ways, it scarcely matters who drew what line on what date. A former Porsche stylist who now heads another automaker’s advanced design explained it recently: great design is accomplished as much with adjectives and metaphors as it is pushing a pencil. It requires good taste and good judgment. It has a final editor who has the executive authority to say, “See! That’s it.” The company delivered the first 901s on October 27, 1964. No one alive at the time imagined what was to become of the cars and their work.

“ It was my father’s wish that I get to know the car body division and simply gather knowledge ‘from scratch’ with the people there and work together with them. I knew Mr. Komenda and Mr. Reimspiess from my childhood, dating back to Gmünd and the old Stuttgart days before the war.” — F. A. Porsche

Previous Page

Page 6

Next Page