Associated albums

FENDING OFF THE VERTICAL LINES “Those were the design parameters,” F. A. explained in 1991. “The 911 was first of all required to have emergency seats . . . jump seats, and there was the rear engine. And there are headlights for the 911, for driving at night. They are markedly more important than it was for, say, the 904. Aerodynamics were given a higher priority in the 904, while the lights were given the priority in the 911.” These were crucial considerations to F. A. the designer. But his role within his father’s company continued to evolve. F. A. found that his greater task was protecting the design staff, blocking the door, keeping out prying eyes, and those with opinions that might bring nothing to the design but certainly would slow and distract his colleagues. “As you can imagine,” F. A. recalled, “there were many people who were interested in the new car, who wanted to see it, who had their own ideas of what it should be.” Chief among those, it turned out, was Erwin Komenda. Within weeks of Klie’s wind tunnel work, Komenda’s team offered Ferry their next candidate on which he drew another metaphorical vertical line in answer to Ferry’s request for a horizontal one again. But worse, while he and the rest of his staff continued designing models for a larger four-seater, Komenda routinely changed the drawings that emerged from Klie’s studio so they reflected his own ideas more closely. Admittedly there were skills, experiences, and techniques—ways to resolve surfaces between bumpers, headlights, and turn signals, as an example—that Komenda’s team knew intimately and that F. A. could not have known even if he had spent 20 years at Ulm, but it went on for more than a year and it steadily became clear to Ferry.

A recent interview with Karl Rabe’s son, Heinz, who has been working on his father’s diaries as a memoir, revealed a turning point in office politics. Komenda was humiliated by this design review. It was his independence, but also his view of the German auto industry, that motivated and inspired him. As Rabe explained, “He never saw the successor as a 2+2 car, always as a four-seater.” In his mind, Ferry Porsche was making a mistake—not being true to his interest in bigger American-type cars. Heinz Rabe knew this because his father Karl was Komenda’s boss in the Konstruktionsbüro Aufbau, always abbreviated in documents as KBA (literally “design department body”).

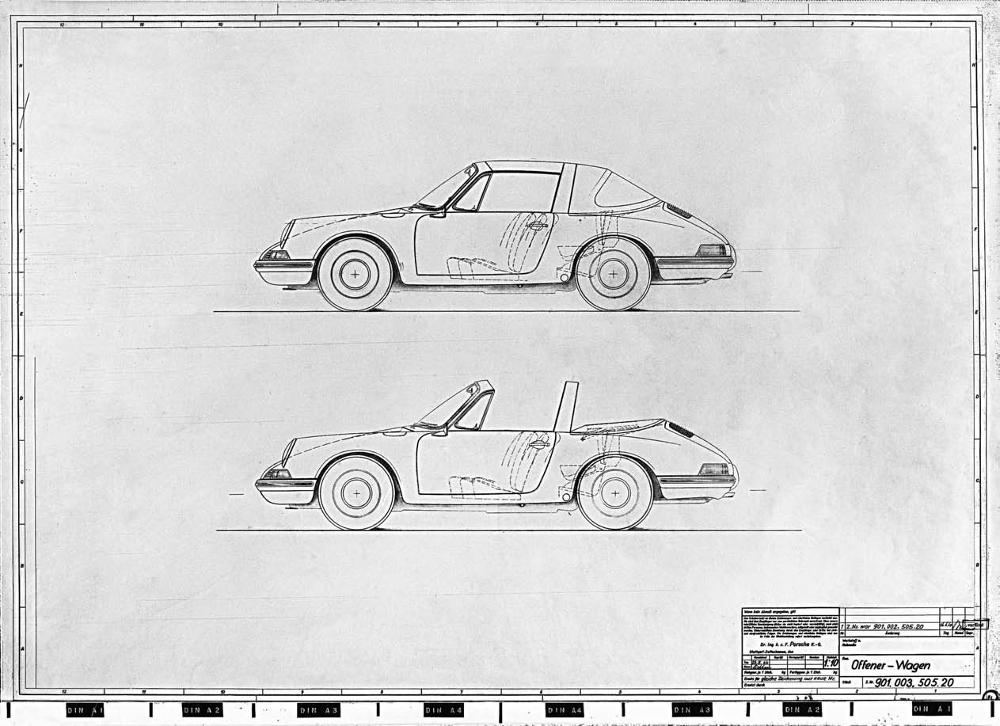

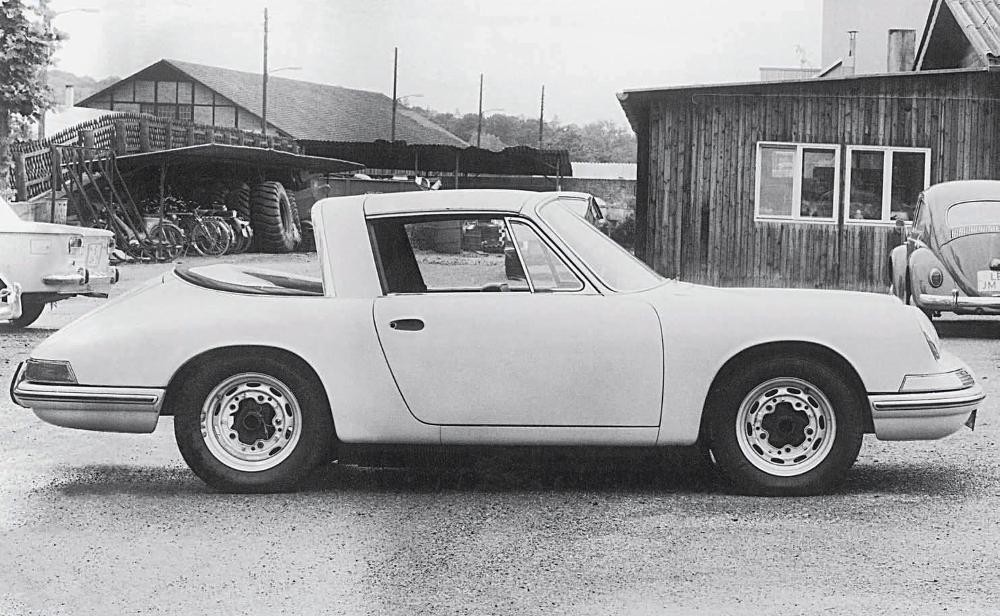

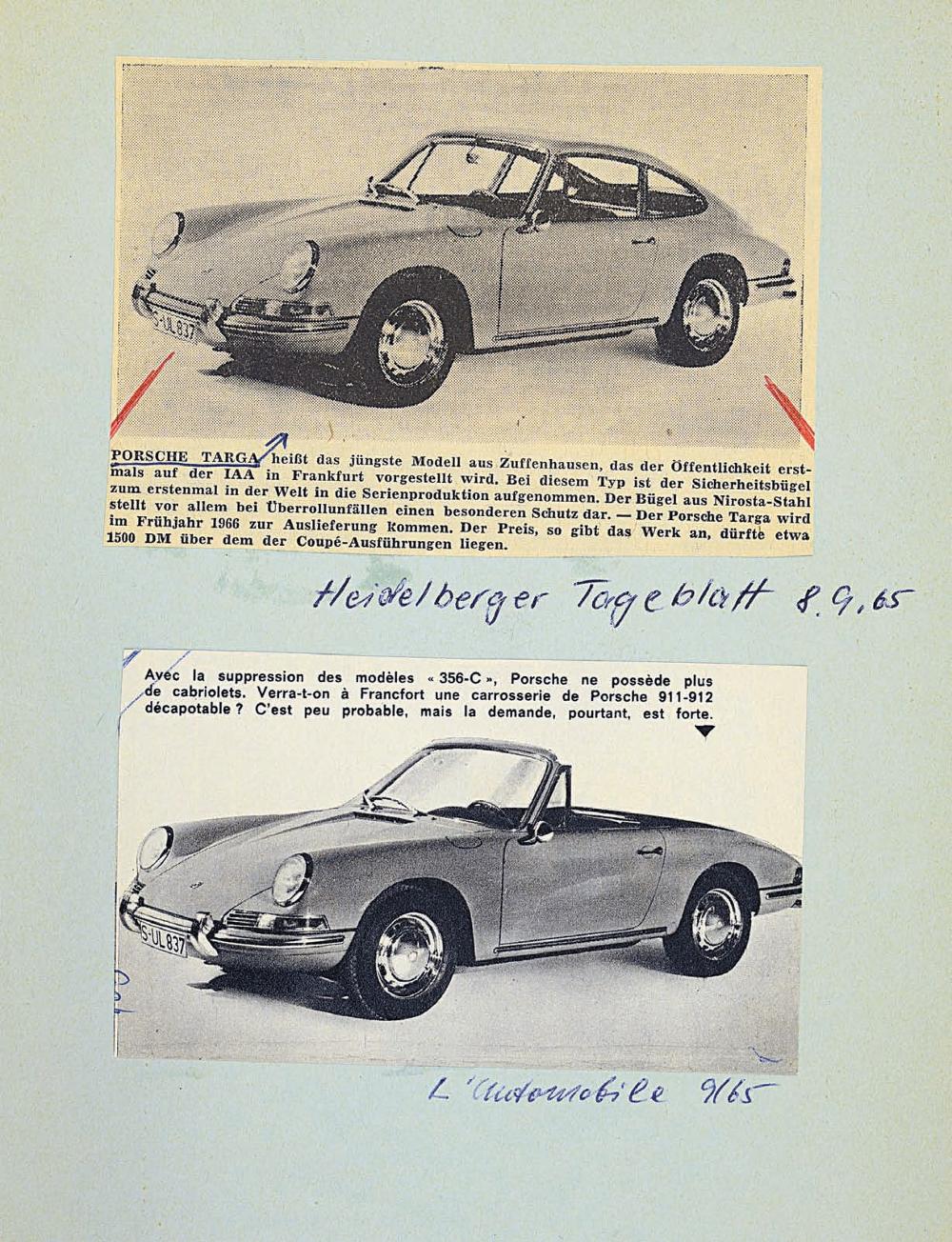

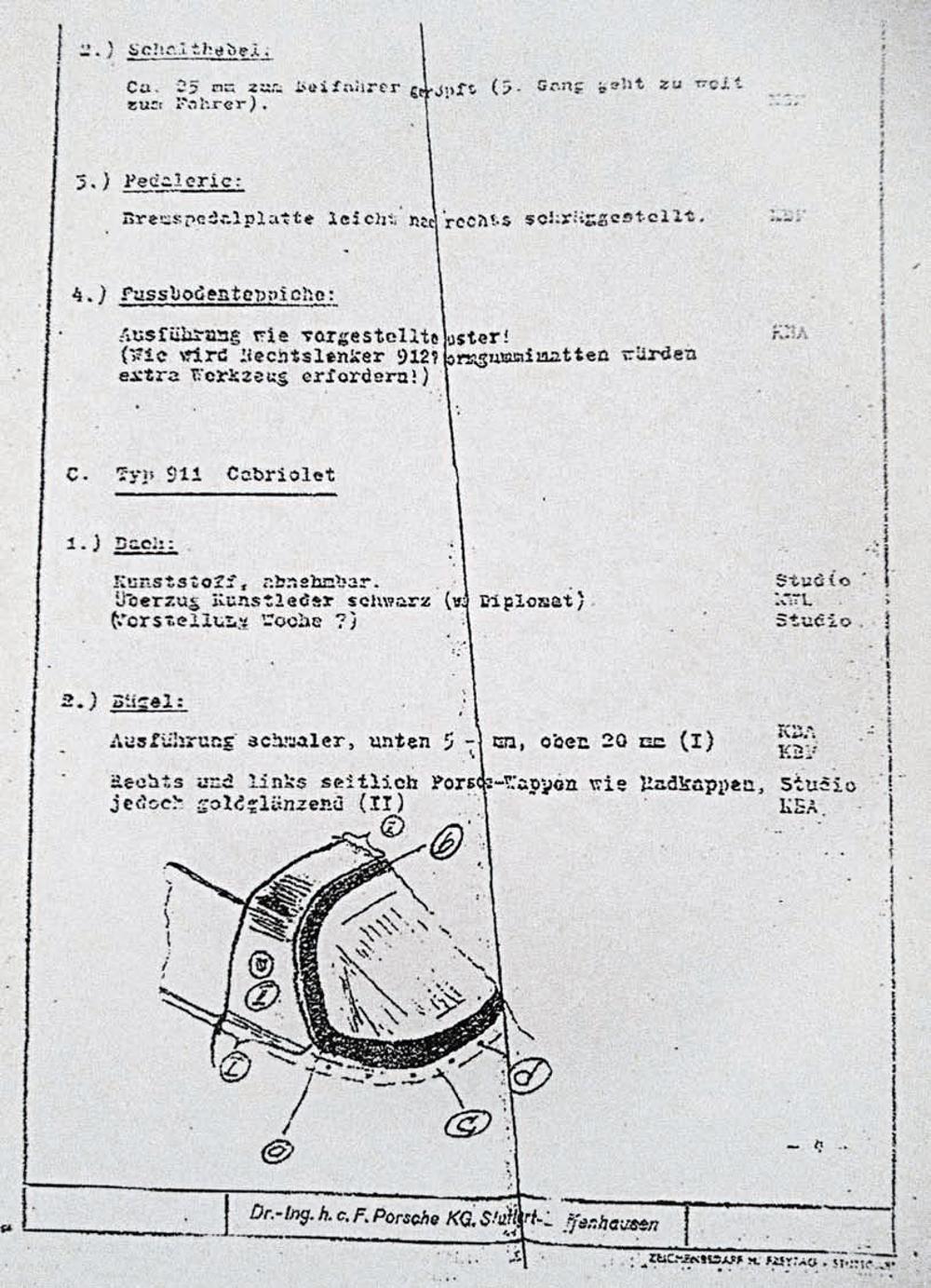

“Ferry understood that Reutter had a department for design and development,” Eugen Kolb went on. “To separate the two competitors at this time, Ferry told Butzi to take the model to Reutter. Reutter and Porsche employees worked on the car side by side and the coordinator was Schröder. This was Ferry’s decision. To keep the peace. Because Komenda wanted to do a bigger body with more space. And Ferry did this because he did not want to have the bigger car.” This was consistent with his publicly espoused philosophy of Porsche’s place in the market: shoemaker, stick to your lasts. As Germany’s sports car producer, he believed he knew his place, whatever his true interests may have been. That day also solidified in Ferry’s mind something he had suspected for a while. The roles of his body construction department and of the design team working with his son were competitive, but not necessarily compatible. As he later told historian Tobias Aichele, “I had to realize that a body designer was not necessarily a styling man, and vice versa.” To Aichele he admitted something more: “Besides which he always changed my son’s styling concepts in the direction represented by him and his team.” Komenda’s independence was no secret. Racer/journalist Paul Frère wrote in his Porsche 911 Story, “Komenda insisted on following his own ideas, rather than the instructions given to him by the head of the company.” Within days of that review, Ferry took steps to protect his styling men and to ensure that his own preferences for the new Porsche prevailed. He contacted Walter Beierbach, Reutter’s managing director next door to Porsche’s Werks. Ferry wondered if they had room in their body development studio to help Klie’s designers finish a project. Beierbach responded quickly. As Aichele reported, on October 20, 1961, Reutter assumed responsibility for developing “the approved T8 body on the T6 [356] chassis, assuming a production start in July 1963.” Three days later, Porsche asked Beierbach to “study options for delivering a simplified and lower cost cabriolet, which can fill the market niche of the discontinued Roadster.”

About three weeks after that, Ferry took everything a step further. Hans Tomala issued an interoffice memo on November 10, 1961. Referring to the Typ 644 T8, it read in part: The model is provided as a two-seater, the rear seat space under the luggage compartment is released for the [fuel] tank. This will leave a much larger, accessible front luggage compartment. In addition, the rear window is to be made as an opening flap [hatchback] whereby the rear luggage compartment is externally accessible . . . The installation of a sunroof is not provided. However, in parallel with the coupe a cabriolet is to be developed. The body style of the new type is being developed by the Styling Department; Mr. Porsche Jr., and all the documents are made available to the company Reutter. As liaison and staff of Porsche, Herr Schröder is available to Reutter. In this capacity, he is under Herr Beierbach, who is responsible for development. Ferry set an ambitious deadline for all this work. He wanted series production of this new car to begin in July 1963, just 20 months away. The following day, Schröder moved with the designs and models to Reutter’s. For the next six months, working in a basement studio, he and a few Reutter technicians completed development of the new Porsche. To further insulate the model department from interference, Ferry made another decisive move: He named his son head of the design department. Heinrich Klie, who had been Porsche’s head of design in all but title, slipped to second spot. As Heinz Rabe explained, “All the familiar Porsche employees, Klie, Ploch, and Schröder, all worked in the new F. A. department.” This was the next logical step in F. A.’s management training that had begun the day he returned from school in Ulm. Komenda retained his title and influence as head of KBA, the body design department, the group that developed designs into cars that could be manufactured. In his role as body developer of the T8 while at Reutter, Gerhard Schröder, strictly speaking, still worked for Komenda’s department. His loyalties, however, had shifted elsewhere. Within days Ferry transferred two engineers, Theo Bauer and Werner Trenkler, into the design department. His idea was for engineers to work for his son and alongside the designers so as their creative renderings appeared, there were accurate engineering drawings that bore unadulterated witness to the concepts as they emerged. What’s more, with engineers in his department, F. A. got minute-by-minute feedback on the practicality of their ideas.

As Aichele learned, “The engineers had been referring to the model makers as ‘mudscrapers’ and had not taken the department seriously. . . . Butzi’s intent was to prevent the design and development team from shooting down a concept on the ground that it ‘couldn’t be done.’” F. A. explained it himself in 1991: “The advantage of my times was the fact that I was the son, which can entail advantages and disadvantages. From my time with Mr. Reimspiess, Mr. Hild, Mr. Mimler, I had an understanding of the technical.” He was a “mudscraper” who understood—and could speak—the language of the engineers. Under F. A.’s leadership, the model department took on credibility it hadn’t enjoyed before. He seized the advantage, issuing his own inter-office memo that read: “If there is to be a required change on existing studio designs, any department involved first is to obtain studio approval.” “People [paid] more attention to what I said,” he explained, “due to the fact that I was the son and had a direct line to the boss. I would be able to work out a proposition, put it in front of him, and say: ‘See, that’s it.’” The concept became the Typ 644 T8, designed on a 2,100-millimeter wheelbase as a two-seater. Because of the need to carry over the 356 front suspension into the new car, a configuration that limited front luggage space, F. A.’s staff designed the T8 with its fuel tank in the rear. Ferry, who was watching Deutschmarks fly out of his offices for racing and testing purposes, hoped to hold costs somewhere and he threw a challenge to his engineering staff that the T8 body should cost no more than the T6 just introduced on the 356B cars. This tied some hands, including Leopold Schmid who was design chief for engines and suspensions, and his development engineer Helmuth Bott. In a meeting January 11, 1962, Bott declared that it was impossible to design and develop a new front suspension in time for July 1963 production. Schmid proposed that they adopt the 356 system, but with ball joints allowing longer suspension travel than the 356’s king pins had provided. Yet Ferry and Hans Tomala argued that although Porsche engineers had created a long-lived 356, a modern suspension was vital for the new car. How the T8 rode and handled had to be adaptable for as many years as the 356 had flourished. Four days later, on January 15, Helmut Rombold, head of the test driving department, reported that the rack-and-pinion steering system he developed for the Typ 804 Formula One car not only improved response and turn in for the new production prototypes, but also offered the company a chance to provide left- or right-hand drive models without changing the chassis. What’s more, with its articulated steering column, it did not move into the passenger compartment in a frontend crash. At this point, all those involved with the new car took a breath and reconsidered what they had accomplished and what remained on their lists. On January 24, Tomala summed up the new thinking on the T8. The wheelbase grew 100 millimeters from 2,100 to 2,200, better accommodating the rear “emergency” or jump seats. Front suspension changes provided room to relocate the fuel tank to the front of the car. Meanwhile Beierbach, who had a nearly decade-long working relationship with Komenda, regularly updated the Porsche body man on the progress F. A.’s department was making on the new 2+2. Despite Gerhard Schröder’s best efforts to assure him otherwise, Ferry accepted Komenda’s veto of the opening rear hatch after he and Beierbach convinced Porsche the new body was not rigid enough and the rear hatch would rattle. Komenda further unsettled the time schedule. On January 31, 1962, two weeks after Rombold’s rack-and-pinion steering introduction, he submitted to Ferry three new full-size wood, metal, and glass models painted as finished cars on the Typ 754 chassis, the T9/1, T9/2, and T9/3. Ironically, these concepts suffered as had Albrecht Goertz’s models, from being more Komenda than Porsche. What Klie’s team had shown Ferry hinted at the Industrial Design influence that directed everything in the 1960s; Komenda’s cars held onto the 1950s. His cars grew in size and bulk with full rear seating, and their details, atypical of Komenda’s earlier work, were fussy and unresolved.

“People [paid] more attention to what I said due to the fact that I was the son and had a direct line to the boss. I would be able to work out a proposition, put it in front of him, and say: ‘See, that’s it.’” — F. A. Porsche

Previous Page

Page 5

Next Page