Associated albums

“We had to go to chassis engineers to find out from them who to contact in metal suppliers to select the material for lightweight bows. We didn’t know any of this. They told us since we had such a hurry that we should hire another 20 men to file off the sharp edges of the bows for each car if we hoped to meet Mr. Schutz’s deadline. “Cracks are a critical concern in cast parts. In a sharp line, there may occur cracks. In a forged part with rounder edges, they last longer. The main bow was die cast, but the main levers were forged aluminum. Schröder developed the front bow and this was an aluminum extrusion profile. That was critical for keeping the line of the top,” he explained. “The front bow is connected to the main bow by a lever and it is attached to the cloth. The main bow is very wide, maybe 20 centimeters, like the Targa, and there the cloth is glued in place. In addition, there are ropes, straps, from the front bow to the rear, connected to the cloth and to strong springs to hold down the cloth. “For Bott it was important to be able to open the rear window without taking down the roof. Like the idea of the first Targa, for the open feel, but also, if you have scratches on it, you can change it without having to replace the entire roof. Schröder made a prototype with electric window lifts and that was the basis for how we could do the Cabrio electric roof.” From Schutz’s discovery of Bott’s Speedster to the Frankfurt debut on September 4 was barely seven months. Six months later, on March 4 when the Geneva Salon de l’Auto opened, engineers were, as Kolb put it, awake to Schutz’s goals. The 18 months from project approval in April 1981 to the Cabrio introduction in late 1982 was considerably less time than the engineers routinely needed. However, both Schutz and Bott had guessed right in their assessment that an open 911 added sales: Porsche assembled 4,096 of the new open cars in its first year, increasing total 911 production by nearly 50 percent. It had taken reorganization and a massive commitment. Bott assigned 911-development responsibility to Friedrich Bezner, and Schutz and the supervisory board devoted the largest portion of the year’s development funding to the 911.

THE DEPARTMENT FOR THOSE WISHING FOR SPECIAL CARS For 1983, engineer Rolf Sprenger’s special wishes Sonderwunsch program introduced the first of his department’s special options, the slant nose, or flachtbau front end for 930 Turbo models. Earliest versions went only to the company’s best customers starting in 1979. These had four rectangular headlights fitted in pairs below the front bumper. A second version incorporated two larger round headlights on either side of a low-mounted oil cooler. This raised eyebrows at the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT), which worried about oil spills in front-end collisions. The third version, with flip-up headlights adapted from the new 944, satisfied all nations for impact safety and lens height. “There are some people who do not like this conversion so much,” Sprenger allowed several years ago. “And others are very much enthusiastic about it. It is a matter of, how do you say, personal tastes? We also very much wanted to change the real spoiler at that time. Because we thought for the whole car it would be nice to have a different rear spoiler. But there was no technical adjustment for the thermodynamic. The Weissach people couldn’t give us another rear spoiler. We had very many more ideas how to change the car in the back.” Sonderwunsch also offered modifications to improve not only the Turbo’s “show,” but also its go, with a performance option that fitted a larger turbocharger, an increased-flow intercooler, and a four-pipe exhaust system. This took output to 330 horsepower and launched the car from 0 to 100 kilometers per hour in 5.2 seconds. With its slightly more aero-efficient front end, the performance option slant nose topped out at 171 miles per hour.

Despite the glitz and excitement of the new open 911, Porsche had plenty to offer with the rest of its 1982 and 1983 SC and Turbo lineups. A year before the Cabrio appeared, the company offered a 50th anniversary 911, commemorating Porsche Engineering’s birth in 1931. Only 200 examples emerged from Zuffenhausen assembly, each finished in Meteor Metallic with burgundy leather and cloth interiors. For those wishing for a slightly bolder presence that also included the beneficial effects of its aerodynamics improvements, Porsche offered SC buyers the option of adding the Turbo front spoiler and rear wing. THE RETURN OF FERRY PORSCHE During this time, Peter Schutz not only waged a battle to reestablish the 911 as Porsche’s most important model, but he also worked to reestablish Ferry as Porsche’s most important asset. When Schutz reached Zuffenhausen in January 1981, he saw accountants working in a large room across the hall from his own office. He knew Ferry had taken a small workspace at Ludwigsburg, and he moved out the accountants and had the area remodeled into a comfortable glass case–lined office for Ferry. “I moved Ferry in there,” Schutz explained in 2012, “and every morning, shortly after nine o’clock when he got there, I’d walk across the hall and have coffee with him.” It became a routine that allowed the newcomer to learn the history from the man who had made much of it. “He didn’t like talking about the past,” Schutz continued. “He was much more excited about the future.” For Ferry and for Porsche, there appeared to be a future. During this period the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the German Deutschmark worked in Porsche’s favor. Through 1982 and 1983, one dollar purchased 2.26 and then 2.43 DM, where in 1980, it had skidded down to 1.82, an exchange that made Porsche cars more expensive in their largest market across the Atlantic. The company introduced the Carrera 3.2 Series for 1984. These improved G Series models fitted the Turbo’s longer crankshaft stroke—74.4 millimeters—while carrying over the SC engine bore of 95 millimeters. The result was displacement of 3,164cc. Bosch mated its latest L-Jetronic system with its new digital motor electronics (DME) Motronics 2 engine management hardware to increase performance and fuel economy while cutting exhaust emissions. To resolve another Schutz—and older owner—frustration, both the 3.2 normally aspirated Carrera engine and the 3.3 Turbo received new oil-fed camshaft drive-chain tensioners.

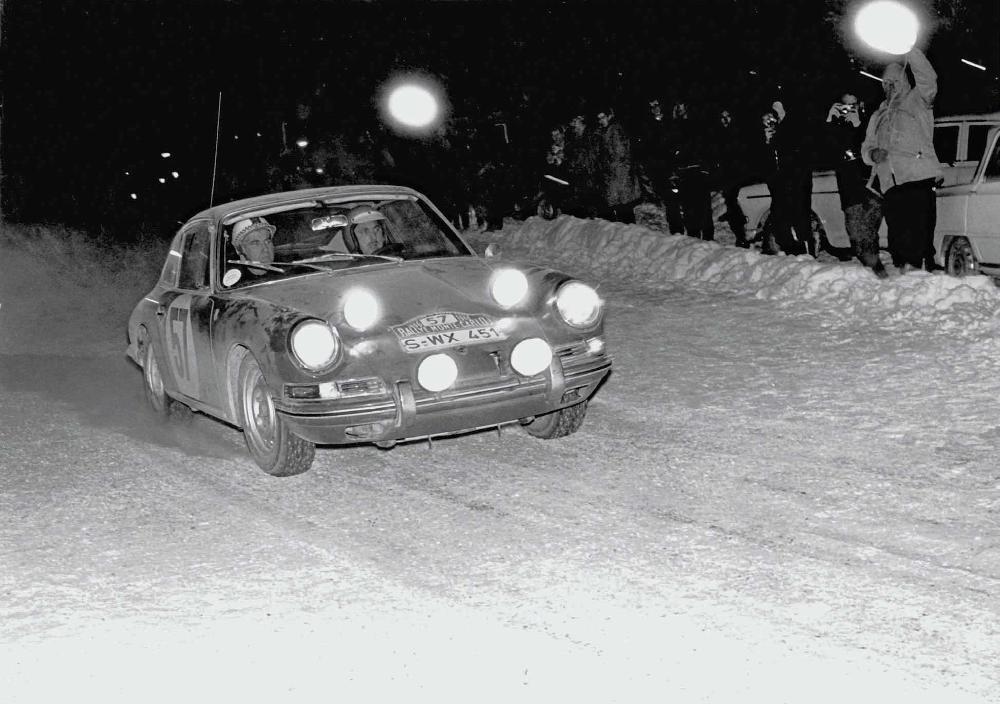

The Turbo remained unobtainable for U.S. customers while the rest of the world enjoyed its power and exclusivity. A “gray market,” so nicknamed for creative interpretation of the spaces between the black-and-white rules for U.S. importation, had blossomed soon after the Turbo disappeared from American dealerships. A number of independent mechanics and body shops collaborated to import non-U.S. specification cars from Europe. The shops had to accomplish a considerable amount of work on each vehicle to meet USDOT and Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations. Some cars worked well; others did not. The marketplace fed an appetite but caveat emptor—buyer beware—was the best advice of the day. Encouraged by Peter Schutz’s embrace of his visions for the 911, Helmuth Bott launched a more ambitious program. His goal was to take the four-wheel-drive system he’d mounted beneath the Frankfurt and Geneva concept cabriolets and put it on the road for Porsche customers. Since the beginning as a car company, Porsche had proved and promoted its products through competition. Nothing forced engineering solutions more effectively than a new race next weekend. Newspaper and magazine stories about racing victories appeared after each event, generating the additional benefit of no-extra-cost publicity. Ferdinand Piëch embraced competition during his days at Porsche and even more effectively as developer and champion of the all-wheel-drive Quattro rally and road cars. For Bott, this was essential technology for the 911. Bott had joined Porsche back in 1952. His earliest assignments were to solve problems with the new synchromesh transmissions, and then he went on to improve road holding for the 356A models. Handling and traction became a lifelong study and fascination for him. Testing one afternoon with factory race driver Richard von Frankenberg, they compared driving styles; von Frankenberg preferred cars with oversteer and he worked the steering wheel, “sawing” it back and forth as he flung the car around corners. Bott preferred near-neutral handling. They had a course set on Malmsheim airfield in the early days before Weissach, and von Frankenberg bet Bott ten bottles of wine that his sawing technique was faster around the track.

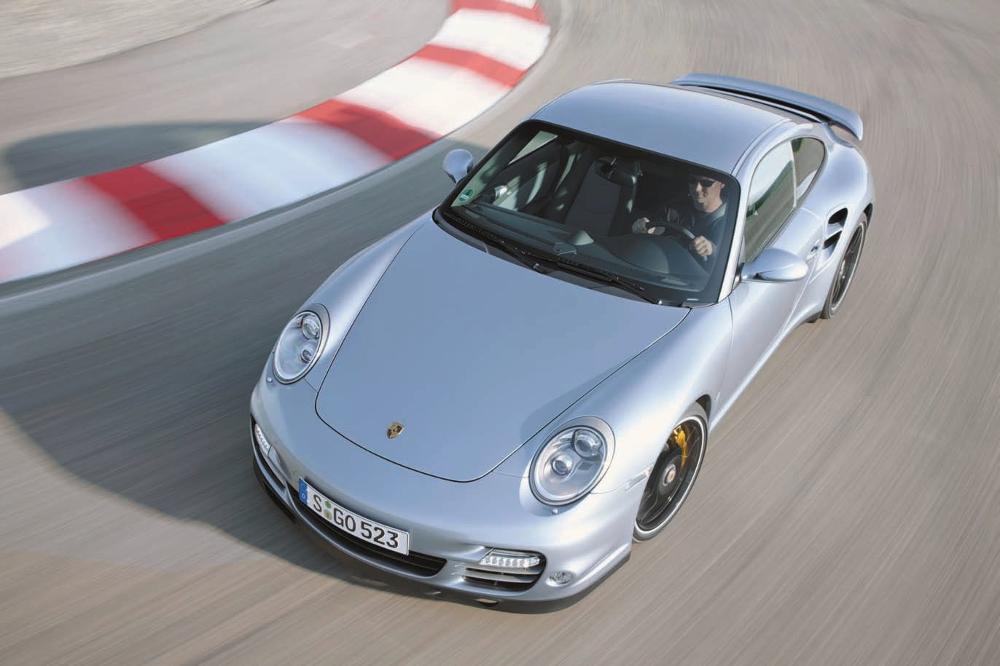

“I passed him two times in 15 laps,” Bott explained in 1992. “He was very upset. I suggested he take the other car, that we trade. So he learned. Because if you have too much oversteer, your front wheels really are not working. And you get much better cornering forces if you take the forces with all four tires. As much more as you are able to distribute your power onto four wheels, the faster you can go through the corner.” Throughout his career, Bott said, his goal was that any Porsche “should have road holding so that everybody can go fast in it.” He continued. “I’m a machinenbauer, an engineer who makes machines. And you know the engineers who build machines are sometimes fighting against the electricians, against the engineers from other faculties. However, when I first saw what you could do with electronics on the engine management, I was so impressed. It thought this was a revolution for the whole car. For everything.” Electronics enabled Bott and a phalanx of engineers and development drivers to create the all-wheel-drive Porsche, the 953 for off-road racing, and later the 959 for the paved roads. These vehicles gave new meaning to the objective of distributing power and cornering forces onto all four wheels. Bott’s engineer Manfred Bantle managed the staff that investigated every technology available at the time, from tires to engine fuel delivery to prototype gearboxes. Bott wasn’t trying to see 20 or 30 years ahead to some far-off far-out technology. He knew his engineers’ capabilities. When Bott targeted a point 10 years out, they frequently had reached it in two. He envisioned racing an all-wheel-drive 911 in the African desert—a competition not unlike the earlier Can-Am and InterSerie with few limits and limitless opportunities for learning. He planned to assemble a production run of 200 vehicles to legalize it for this competition. He understood Porsche’s customer base and remembered that sales of the 1973 Carrera RS had tripled what the company needed for homologation. If Zuffenhausen could assemble 200 of these four-wheel-drive cars, they also could make many more from what they learned if the demand surged. From the styling department, staff designer Dick Soderberg got the assignment to create Bott’s 911 for ten years down the road. He hoped the company would allow a new roof—one of the most costly features on any automobile—sharing a conviction with Bott and Bantle that the 959 should emerge without spoilers and wings. Without that investment, though, a rear wing was an aerodynamic necessity, especially for a car with the speed potential the engineers envisioned. In the end, the integrated rear wing that Soderberg devised with aerodynamicist Herman Wurst, what Wurst called the bread basket handle, created a design language that other car stylists adopted, and it tweaked the over-roof airflow to hug the car body. A long slender black lip, added onto the rear deck lid just before production started, fine tuned the aerodynamics and yielded a low coefficient of drag of 0.32 in contrast to the production Carrera coupe at 0.39. Porsche steadfastly supported the Frankfurt IAA show and once again chose the event to unveil its pearlescent-white painted show car in September 1983, identified as Gruppe B. The company promised production for 1984/1985. However, with all the complex systems, and the new technologies and materials incorporated into the car, that target slipped again and again. The engine and drivetrain for this new car proved to be an engineering tour de force, partially because Bantle and Bott were aware of expectations. As historian Karl Ludvigsen reported, Bantle wrote a memo acknowledging that the technological community in Germany would accept only “typically Porsche perfection of the four-wheel drive technology.” In 1978, racing engineers, faced with the need for more horsepower, developed water-cooled cylinder heads for some of the 935 race cars derived from the road-going 930 Turbos. This system allowed them to fit four valves per cylinder under those dual overhead camshafts; this provided “breathing” capability that was impossible in air-cooled engines. For the 959, dual turbochargers developed progressive boost that delivered 450 horsepower at 6,500 rpm from the 2,849cc flat six. Bore and stroke measured 95 millimeters by 65 millimeters. Exchange rates between the U.S. dollar and the Deutschmark continued to make U.S. sales valuable, and, for Porsche’s board, such continued investment seemed reasonable. The average rate through 1984 was 2.85 to the dollar and through 1985 it averaged 2.94. A $48,000 Turbo sent home 60 percent more marks than that sum provided in 1980. Company profits for 1985 were 30 percent higher than in 1984. Porsche’s sales in the United States consumed nearly two-thirds of 1985 total production of 54,458 cars. Schutz approved the 959 launch at the September 1985 IAA show. The company promised deliveries of two versions, a Sport and a Comfort model, in August 1986. It set the price at 420,000 DM, about $143,000 at the time. Porsche demanded 50,000 DM deposits (almost $17,000). Some 250 potential buyers opened their checkbooks; the oversubscription allowed that some customers might step away. From many viewpoints, Peter Schutz looked like a savior.

Through all this 959 development, the company made small, steady changes to the Carrera 3.2 and Turbo 3.3 models. Profits not only had encouraged the showpiece 959, but also allowed further development of the 911, an evolution necessary because of continued safety and emissions regulations updates from a number of governments. “ I moved Ferry in [the office across the hall from mine], and every morning, shortly after nine o’clock when he got there, I’d walk across the hall and have coffee with him.” — Peter Schutz “With the G model, every year we made new things on the car,” Bernd Kahnau explained. Kahnau grew up inside Porsche. His father, head of 356 production, drove him and his mother home in his 356 from the hospital after his birth. “We did gear switches, every year new things. New clock. Vents, mirrors, seats, tires, steering wheels. But the G model was not possible to make ABS, not possible to make airbags.” Those innovations and requirements dictated a new structure. Lessons, developments, technologies, and features spilled over from the 959 to this new vehicle, soon known as the 964.

Previous Page

Page 13

Next Page