Associated albums

Once the testers finished, the ducktail went back to Lapine’s studios to ready it for production. It led to a moment reminiscent of the studio modifications that occurred between Erwin Komenda and F. A. Porsche. Lapine himself made designs of the entire car. When his styling department presented the first actual vehicle—it was just before the production start—Falk was startled. “The burzel is too low! Why is it lower than we tested it?” “Because it looks better,” Lapine told him. Decades later, Falk related that Lapine had cut 10 or 20 centimeters off the height because he thought it had better proportions. It went into production shorter than what Falk and his drivers had wanted. The lip, or “chin spoiler,” appeared on 1972 model-year regular production 911s. Almost immediately even average drivers on American interstates and European autobahns felt the stability improve in the car. But neither Fuhrmann nor Berger was done. Late in 1972, another level of 911 performance and options arrived. Originally (and internally) known as the 911SC, marketing needed something more dynamic and more appealing, and they proposed resurrecting the name Carrera from earlier high-performance 356 models. Tillman Brodbeck’s startling ducktail debuted on the 911 Carrera. The rest of the car’s designation revealed more of its secrets: RS 2.7., a Rennsport-inspired vehicle with a 2.7-liter engine.

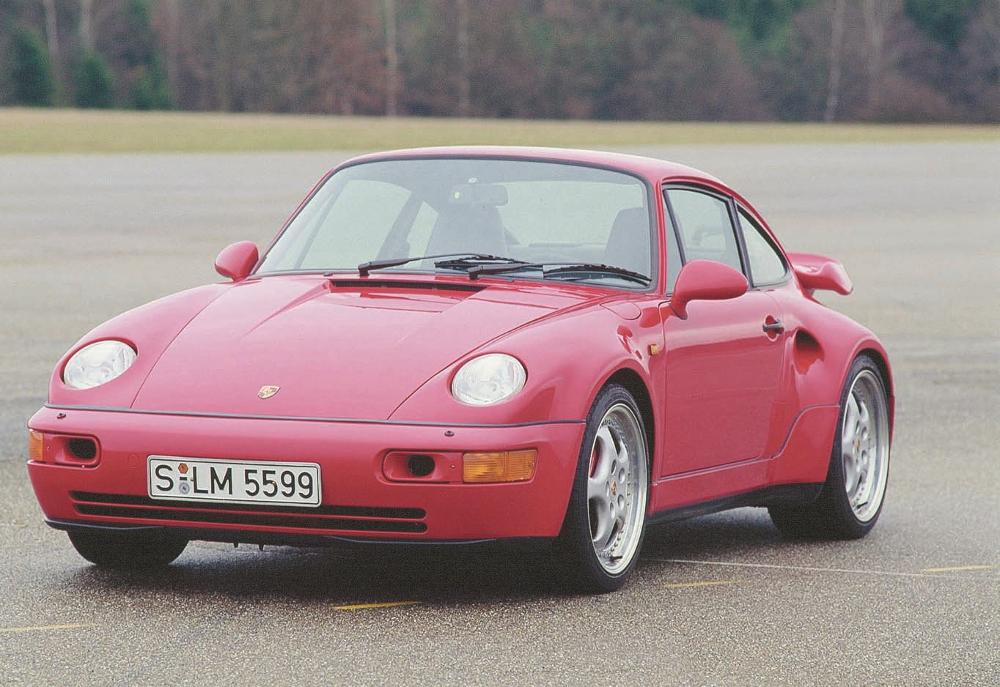

The new model entered the market with the purpose of meeting homologation requirements as a production race car. As such, it took some inspiration from the ultra-limited run of 911R models that Ferdinand Piëch developed in 1967. That series of four prototypes and 20 production cars emerged mainly to determine what the competition limits were from an automobile derived from series production roots. Those 20 production R models remained prototype-category competitors all their lives and accomplished impressive results, but the point of these new RS models was to take back Hockenheim and every other racetrack from those modified Fords and BMWs. Regulations from the Fédération International de l’Automobile (FIA), racing’s international directorship, called for a minimum run of 500 identical cars to qualify for Group 4 Special Grand Touring Car category. For these models, the so-called lightweights, everything nonessential to competition fell from the car, stripping its weight to just 1,984 pounds. Marketing and sales, who had talked Piëch and others out of more than the 20 series 911R models, believed it was impossible for Porsche to sell anywhere near 500 of these spare uncompromising automobiles. To appease them, Bott, Singer, and Berger devised a touring version of the car, fitted with an interior more like the best-equipped S models. These came in at 2,370 pounds. To power the vehicle, Hans Mezger’s engineers developed a new 2,687cc flat six by enlarging bore from 84 millimeters to 90 millimeters. This engine introduced aluminum alloy cylinders with Nikasil liners, a nickel/silicon coating that promoted better cooling and less wear. With Bosch’s K-Jetronic (the K for kontinuierlich, or continuous) electronic fuel injection and ignition management system in use, the engine developed 210 DIN horsepower. Because Mezger conceived the engine for competition, Porsche did not attempt to configure it to meet U.S. emissions standards, rendering the car unobtainable in the States for many years unless it came to race. Word spread that this car was limited in production and something special from Porsche. The mandatory 500 lightweights (designated M471) nearly flew out of Zuffenhausen. (Porsche had sold those first 500 even before they unveiled the car at the October 1972 Paris Auto Salon.) Sales personnel were stunned, and by the time they finished counting their receipts, 1,580 of the RS Carrera models sold in 1973. This gave it FIA eligibility for the far less challenging Series Production Grand Touring Car Group 3 (for which the requirement was 1,000 units), where the Carreras triumphed. The cars sold for 36,000 DM ($13,585 at the time), some 5,000 DM ($1,887) more than the 2.4-liter 911S. The lightweight versions used plastic and/or thinner metal body panels and narrower gauge window glass. One of its most distinctive features was its bold graphic on the sides, the word “Carrera” in script, in a color matching its five-spoke Fuchs wheels. As RS Carrera historians Thomas Gruber and Georg Konradsheim reported in their meticulously researched book, RS Carrera, Porsche took no chances with the homologation. Zuffenhausen assembled not just the first 500, but the first 1,000 cars as their most stark RSH or Rennsport homologation versions, mounted on narrow wheels, with no ducktail. Mechanics drove the cars off the assembly line directly to Stuttgart’s official weigh station. After certification, they returned the cars to Zuffenhausen for completion as the customer ordered it. The lightweights had only a driver’s sun visor, no glove box cover, cardboard door panels with straps operating the latches, and no insulation or sound-deadening material. Customers with no intention ever of racing the cars snapped them up, teaching Porsche marketing and sales a lesson: if we build it, they will come. For those who were unable or unwilling to get a 1973 RS, Porsche carried over the S, E, and T models with their 2.4-liter engines introduced the year before. In the middle of the model year, Porsche introduced the Bosch injection system to T models for American delivery in order to meet coming emissions standards.

THE SECOND GENERATION: THE G MODEL What emerged from Zuffenhausen and Weissach for the 1974 model year was, in some ways, a car the company never intended to make. Strict new regulations from American legislators dictated everything from bumper height to headrests integrated into seats for rear-end collision whiplash restraint; from automatic seatbelts to heavier padding on instrument panels, switches, and the steering wheel hub; from mandatory use of regular-grade unleaded gasoline to the addition of air-cleaning-but-performance-robbing belt-driven devices to the engine. Porsche had to redesign and reconfigure a car they expected instead to discontinue. This was the birth of the well-regarded G Series. Bumpers had perhaps the biggest potential to destroy those hard-fought shapes of the 911. American safety regulations required that those at the front of the car had to withstand a fivemile- per-hour impact with a fixed barrier and show no damage. Styling chief Tony Lapine, who had brought with him Wolfgang Möbius, Dick Soderberg, and chief modeler Peter Reisinger when he joined Porsche from Opel, set them and a variety of chassis engineers to solve the problem. Möbius’ bumpers, with the accordion-like rubber interfaces to the body, met the requirements and retained the car’s balanced proportions. Historian Karl Ludvigsen wrote, “After the G-Series cars had been on the market for about a year, they looked so right and were so familiar to the eye that they tended to make earlier Porsches look excessively light and fragile by comparison.”

Porsche offered the 150-horsepower base 911, the 175-horsepower 911S, and the 210- horsepower Carrera. Carrera buyers in the United States got the S engine in their cars. Displacement was the same—2.7 liters with Bosch electronic fuel injection on the base and S models (and U.S. Carrera), and mechanical injection feeding the European Carrera. Porsche had made history on the world’s endurance racetracks with its effective 917 series of coupes with their opposed 12-cylinder engines. Those cars, however, had strict regulations for engine displacement and other specifications. Elsewhere in Europe, the InterSerie and, across the Atlantic in the United States, the Canadian-American Challenge were racing series that enforced no limits on engine sizes and encouraged unlimited development. Porsche’s response to interest from a couple of its drivers was to turbocharge the flat 12 and mount it in an open Spyder body. In its wildest trim, this technology yielded as much as 1,400 horsepower, more than doubling the normally aspirated output. The InterSerie and Can-Am turbo technology seemed like a fantasy for road cars until Porsche delivered it with a leather interior and electric window lifts. “All my life, all my automobile life,” Ernst Fuhrmann recalled, “I was of the opinion that racing must have a connection to the normal automobile. And we were very successful with the InterSerie in turbocharged cars. And when this race car came, it was noiseless. And the next version was better. So we were far ahead. I said to my people, why don’t we put this success into our car? “They said, ‘Oh, this was tried already.’ “But not in a car that was done right. “‘And it was refused by management in that time! ‘It was impossible,’ they said. ‘There’s not enough room.’ This was my contribution: I looked in the engine and said, ‘There must be room!’” Porsche engineers always looked for ways to increase engine output from an air-cooled flat-six cylinder engine that already was approaching some limits. Engineering protests prior to Fuhrmann’s assignment were nothing compared to the problems they encountered as they struggled to make the systems work. “Herr Binder was the head of engine design department,” Herbert Ampferer recalled. “He came to me and said, ‘You, young guy, you are young, inexperienced. I need a layout designer for the new turbo engine.’” Ampferer was a young guy with a mechanical engineering degree from Steyr in Austria, concentrating mostly on engines. His first job at Porsche put him to work on the EA266 mid-engine project for VW. “It was horribly complicated, drives running around the corners, bent drives. Unbelievably complicated,” he said. Turbo technology in those days, 1970 and 1971, while he and racing colleague Valentin Schäffer worked on road and competition adaptations within Porsche, came mostly from commercial truck applications. These were unsophisticated systems, as can be expected from needs that weren’t centered on any kind of responsiveness. A German named Michael May was turbocharging Ford Capris. The car suffered lengthy turbo lag—the response time from throttle pedal input to engine reaction. Porsche acquired one to give the engineers a sense of the state of the art. Ampferer recalled one drive where by the time the turbo input reached the engine, he was headed at a huge concrete wall: “I made it. Nothing happened. So I had a good test on the lack of response of the turbos.” With that experience in hand, he questioned Binder about the considerations he had to design into Porsche’s turbo car. “Tell me, sir, do we need air conditioning for that car?” Ampferer asked. “‘No, we don’t need it,’ he said. Do we need a rear wiper for that car? ‘No, we don’t need it. This is only 200 cars or something. Forget it!’”

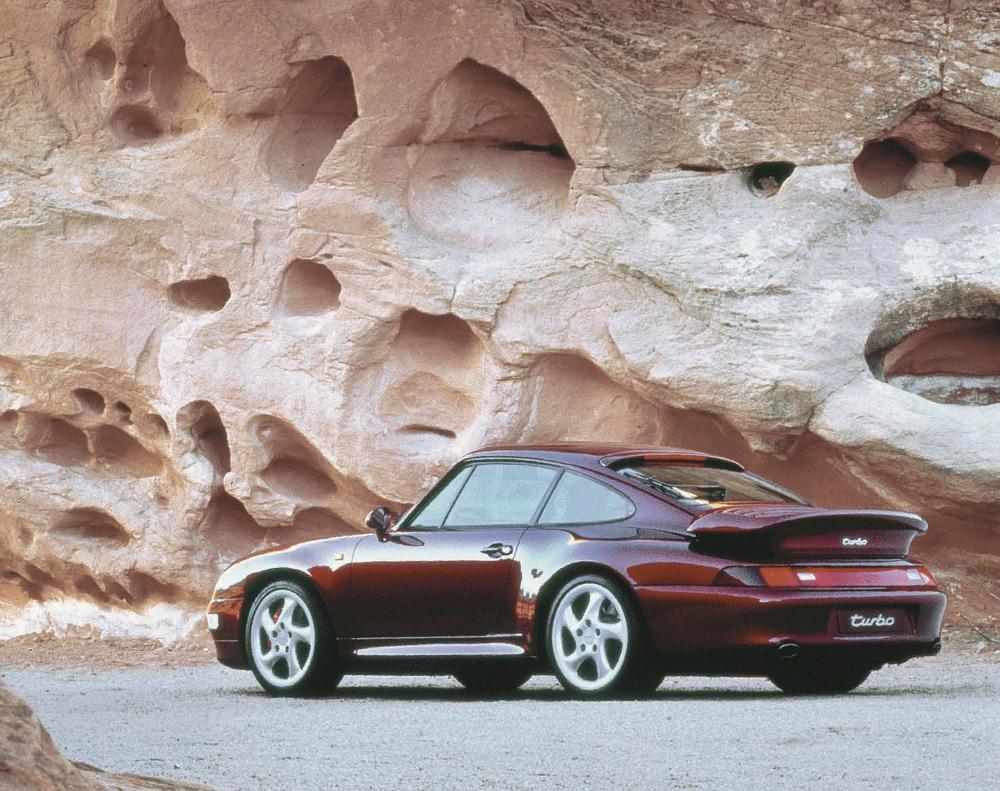

“Then sales and marketing announced that they could sell many more than only 200. And they needed air conditioning. So we started from scratch, completely. It was a case of not knowing what market was in front of us for this new car.” They experimented with prototypes. One used a 2.7-liter block. In 1969, Valentin Schäffer had mounted turbos on two-liter 901 engines. One turbo stuck out of the rear deck lid of a 911 coupe, while another, even though it protruded from the engine compartment of a 914-6, suffered critical cooling problems. To Binder and Ampferer, the three-liter engine developed from the 2.7 for the racing Carrera RS 3.0 seemed a good place to start. “I was involved with the 930,” Ampferer explained, using its internal Typ number, “but once you have designed the components needed for the prototypes, you are a little bit out of the business. Product procurement starts. Product components come in house. They get assembled, and the first tests bring the first calls. ‘We have a problem there, we have a problem here.’ And you redesign it, and it goes again. You are involved in that process just from time to time. You have time to start it along with another project.” For Ampferer, that other project was the front-engine water-cooled Typ 924, the final joint development with Volkswagen under the old contract. Both projects moved through their various phases, the 930 Turbo appearing in the spring of 1975 in Europe. Its 2,994cc engine incorporated a 95-millimeter bore within the aluminum alloy crankcase. With normally aspirated compression at just 6.5:1, when the Kühnle, Kopp & Kausch (KKK) turbocharger spooled up to its 90,000-rpm operating speed, it boosted air into the cylinders at 0.8 bar, 11.3 pounds per square inch (psi). As a result the engine developed 260 horsepower at 5,500 rpm, making the coupe with its prominent rear wing into the fastest German production car of its time. Acceleration from 0 to 100 kilometers per hour took 5.5 seconds, and the car reached a top speed of 155 miles per hour.

“ All my life, all my automobile life, I was of the opinion that racing must have a connection to the normal automobile. And we were very successful with the InterSerie in turbocharged cars. And when this race car came, it was noiseless. And the next version was better. So we were far ahead. I said to my people, why don’t we put this success into our car? They said, ‘Oh, this was tried already.’” — Ernst Fuhrmann

Previous Page

Page 10

Next Page